Pasts Imperfect (9.25.25)

This week, historian of science, art, information, and monsters Surekha Davies discusses monster-making in the past and the present.

This week, historian of science, art, information, and monsters Surekha Davies discusses monster-making in the past and the present. Then, a new comparative (and free) volume on art from ancient India and the Greco-Roman world, Vitellius takes the cake (stand), saving the petroglyphs of the Silk Roads, Barnard professors defend free speech, protecting the Bedouin living in the caves near Petra, ancient world journals, and a call for papers for the next AAH in Iowa City. Finally, Joy Connolly provides a touching eulogy for classicist Michael Putnam.

Ancient Typology and Monstrosity in the Shaping of Racial Hierarchies by Surekha Davies

When people think about monsters in the ancient world they tend to think of the ones within myths — the Minotaur, a chimera, or the Sphinx, perhaps. But monsters were also themes in ancient scientific and religious thought. Not only did the ancients see the boundary between human and monster as unclear, even porous, but their ideas reverberated for centuries, shaping the age of European oceanic expansion from the late fifteenth century and the maps produced thereafter.

Ancient thinkers distinguished between one-off monsters and entire monstrous species. There were three possible reasons behind the birth of one-off monsters. The first, outlined by the statesman and thinker Cicero in his influential On Divination (44 BCE), was that a human or animal monstrous birth was a prodigy or a portent of impending doom or perhaps a punishment from the gods. The second, described by the naturalist Aristotle in his Generation of Animals (c. 350 BCE), was that a monstrous birth was the inevitable consequence of nature attempting to impose its will on physical matter which sometimes resisted, leading to a less-than-perfect result. The third reason was simply that nature sometimes made jokes.

What counted as a one-off monster? First was any being that didn’t resemble its parents, particularly its father. In Aristotle’s view, this made women automatically something of a failure since they hadn’t been born as men. (He did, however, grant that women were necessary for perpetuating the species.) What’s more, since no one had any idea what went on in the womb, women were also potential monster incubators.

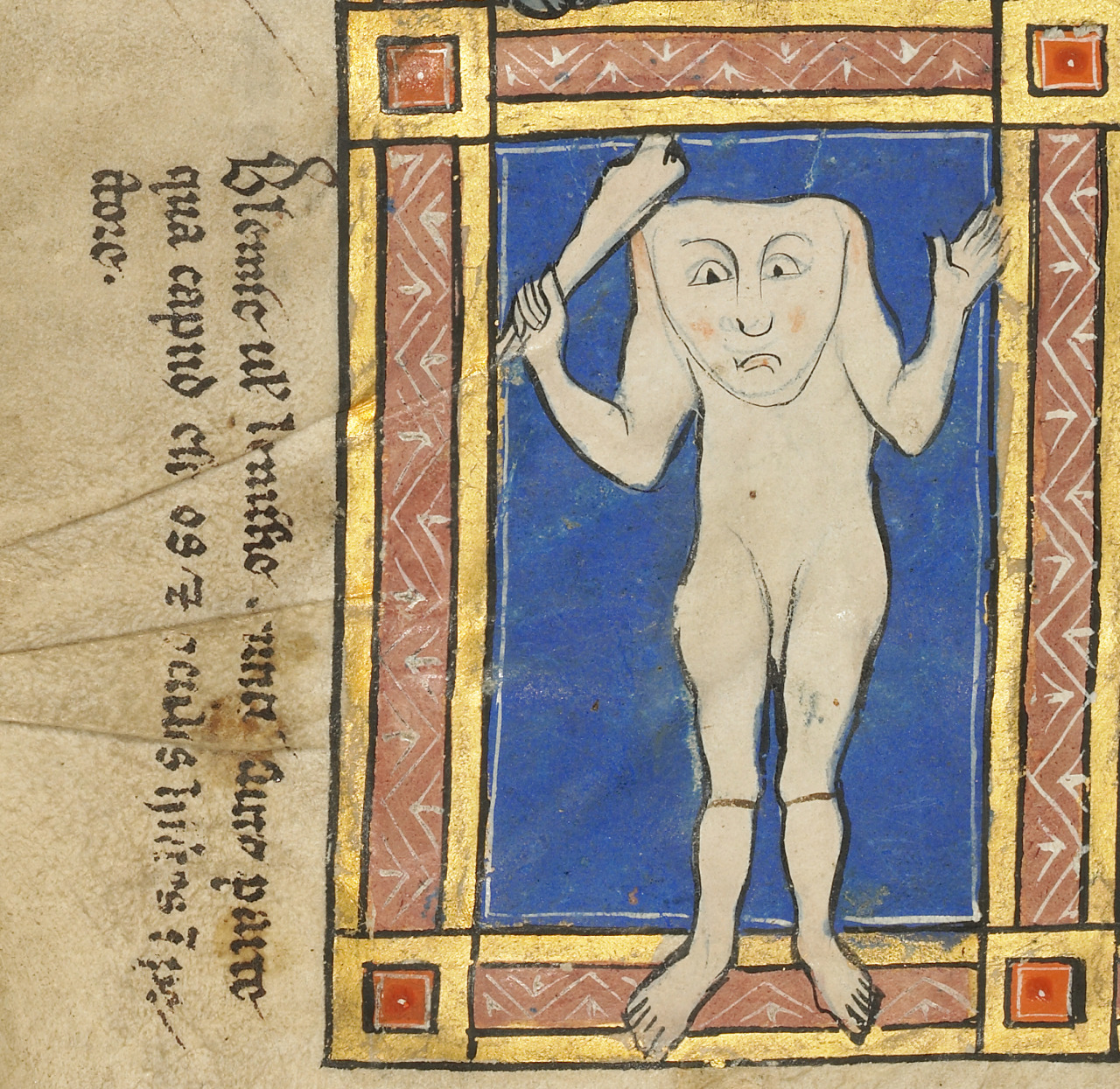

In addition to one-off monstrous births, which were atypical compared to other beings among their kin, ancient thinkers also understood that there were regions where monsters were normal. Geographers theorized that in places most distant from the comfy climate of the Mediterranean - those places where the weather truly sucked - the effect of the climate on humoral - one might say squishy - bodies was that they took monstrous forms or behaved in monstrous ways. Entire communities who supposedly shared a monstrous characteristic were called monstrous peoples. The Greek chronicler Herodotus and the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder recounted how monstrous peoples like the Blemmyae lived in Asia and Africa. There were, for example, the Panotii (Plin. NH 4.95), who lived in an exceptionally fertile region which gave them unusually long ears. Troglodytes, on the other hand, dealt with the harsh climate of their lands by hiding out in caves.

In ancient biology and medicine, the body contained four essential substances known as humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. These humors performed a delicate dance to stay in balance and keep a person healthy. But they were susceptible to the world beyond the skin: what a person ate, the climate in which they were born and lived, the seasons, and their physical activities influenced the balance of humors. Since the humors were variable, bodies and temperaments were malleable. This meant that monsterliness wasn’t necessarily a risk that was over and done with at birth.

In medieval Europe, theologians, physicians, and philosophers filtered and expanded ancient knowledge about geography, natural history, and medicine using a sieve shaped by Jewish, Christian, and Islamicate textual authorities. Medieval manuscripts devoted to travel, geography, or natural history frequently include depictions of monstrous peoples. Biblical scripture offered possible explanations for monstrous peoples. Cain, for example, who had killed his brother Abel, was believed to have had a divine curse laid upon him. This curse deformed his descendants. Some of Cain’s kin who survived the Biblical flood were thought to have been imprisoned by mountains brought down around them by God; Alexander the Great was said to have walled up the only mountain pass. Their tribes, known as Gog and Magog, appear on medieval maps behind Alexander’s wall.

In terms of cartography, medieval world maps depicted monstrous peoples at the edges of the earth, and show the continuing classical traditions informing geographical thought. Where was the boundary between human space and monster space? And what would happen if someone conventionally human travelled to or settled in a place with a monstrifying climate? These were questions that the ancients and medievals didn’t especially need to answer since they weren’t crossing oceans.

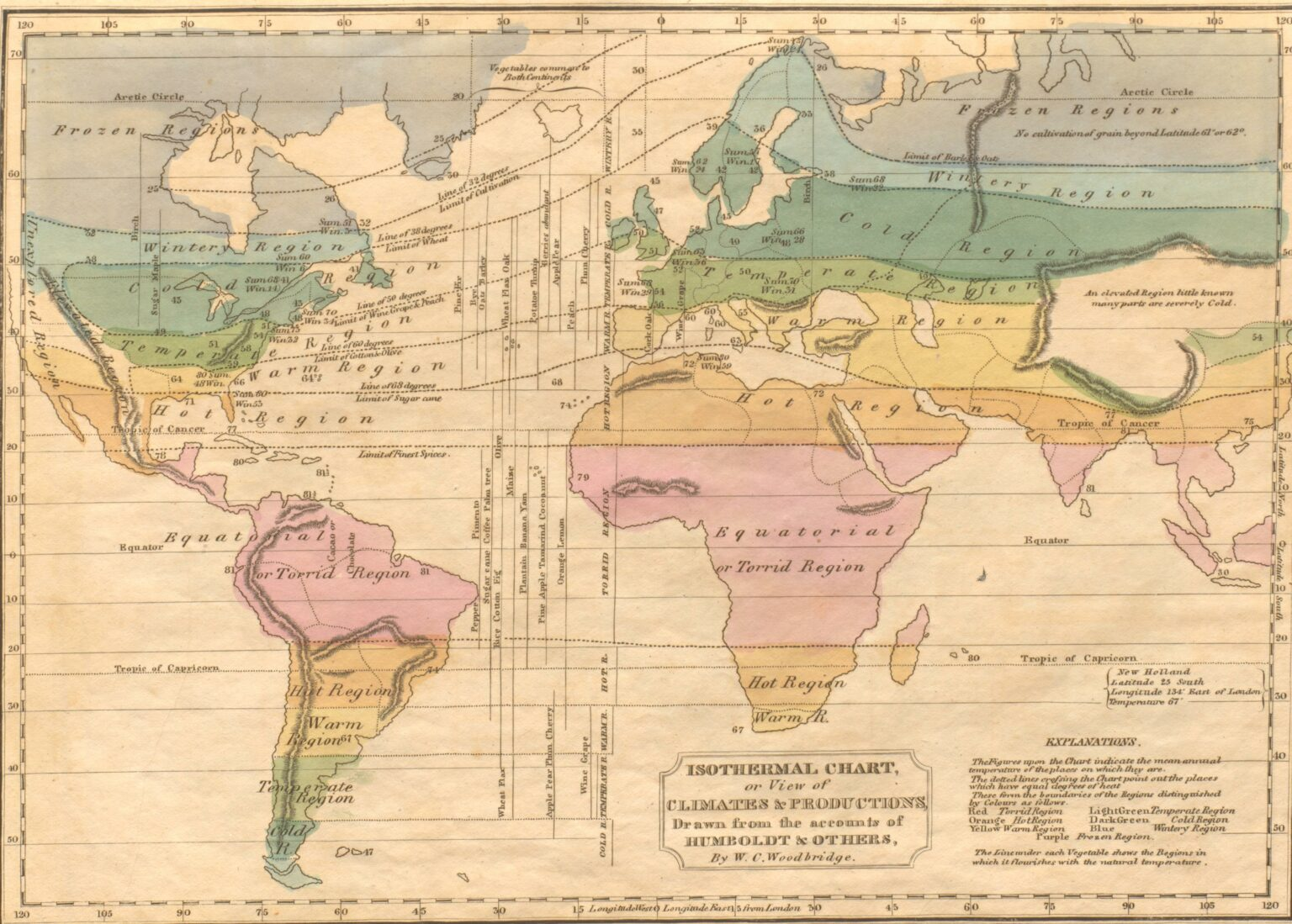

Two changes in the fifteenth century made these questions timely. First, the re-discovery of the 2nd century CE Greco-Egyptian geographer Ptolemy’s Geographia and its dissemination in print prompted a shift from world maps that placed Jerusalem in the center to maps drawn using latitude and longitude coordinates. These maps made it easier to compare the relative distance of places from the temperate region of the Mediterranean, and to compare relative latitudes of different, distant places.

The second change from the late fifteenth century was transoceanic travel and the ensuing settling of people from Europe in the Caribbean, the Americas more broadly, and beyond. Suddenly, the squishiness of humoral bodies had potentially monstrous consequences for Europeans, and implications for any attempts at colonization. In the increasingly interconnected Atlantic world, there was an existential need to re-write stories about race and the innate essences of bodies before there was an economic one.

Sixteenth-century world maps that projected the world on a grid made implicit claims about the relationship between bodies, societies and geographical locations. Images of monstrous peoples placed in particular locations on a map implied that the local people were monstrous. Implicitly, there was a belief that the local climate might turn out to be a monstrifying one.

The monsters of classical antiquity linger. In the age of European empires and settler colonialism that followed the Middle Ages, they shaped how colonial administrators, theologians, physicians, and naturalists characterized, treated, and administered subject peoples and enslaved people. Ideas about monsters informed theories about race and expanded systems of racial hierarchy with effects that still reverberate today. And people still speak of child prodigies albeit to mean individuals who exhibit uncanny levels of talent rather than precursors of divine plagues. Not only can we never truly be modern but we are still, apparently, also ancient.

Dr. Surekha Davies is an award-winning historian of science, the author of Humans: A Monstrous History (University of California Press, 2025), and writes the newsletter Strange and Wondrous: Notes From a Science Historian.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

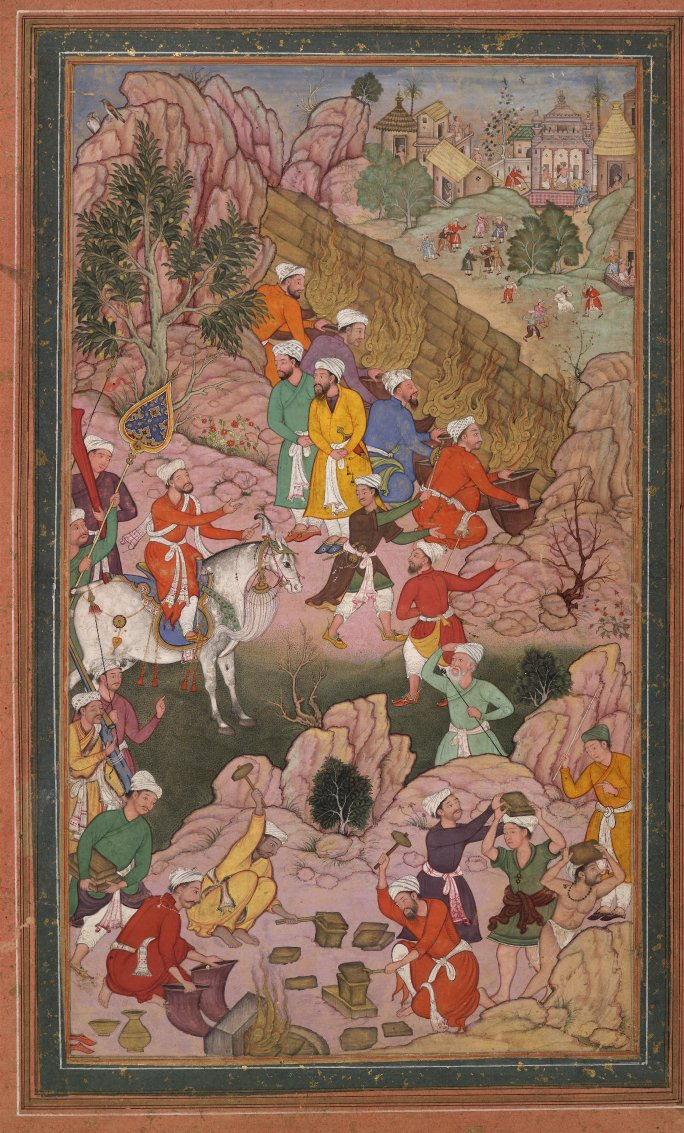

A new, open access volume on Classical Art and Ancient India, edited by art historian Peter Stewart, is now available. There are some impressive chapters covering everything from the "Romano-Egyptian Connection to the early Buddhist art of South and Central Asia" penned by William Dalrymple to Sunil Gupta's cool chapter on "Art along Ancient Indian Trade Routes (3rd century BC to 5th century AD)." You never do know just when Hercules or a Trojan Horse will pop up.

On the book review front, classicist and esteemed cat-lover Gregory Hays has a new review in the New York Review of Books of Mary Beard's Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern and Emperor of Rome: Ruling the Ancient Roman World, along with Peter Stothard's newly penned Palatine: An Alternative History of the Caesars. I admit that I have never learned so much about cake dishes and Vitellius.

Look, most of us have a deep case of tsundoku (積ん読)—the joyous habit of buying books we don't read—but we do hope you dig into a few of these. First, scholar of early Christianity Jennifer Barry has a new book out with UC Press on Gender Violence in Late Antiquity: Male Fantasies and the Christian Imagination. Classicist Marchella Ward has an open access article on "How the Past Became a Weapon of Genocide in Palestine" and the excellent new volume in the Antiquity in Global Context series at Cambridge University Press is out digitally. Leadership in the Ancient World: Concepts, Models, Theories is a sweeping but pedagogically useful volume that looks at global ancient leadership standards and tactics in Ancient Mesopotamia, Pharaonic Egypt, in Ancient China and among the Achaemenids, Classical Athens, Judaism, and Ancient Rome.

Anita Anand and William Dalrymple's Empire Podcast has begun a new series on the history of Gaza, and two episodes on the region's ancient history featuring Josephine Quinn, Professor of Ancient History at Cambridge, have already dropped. At the Quirks and Quarks podcast, academics Jason Neelis and Ali Zaidi from Wilfrid Laurier University discuss the Silk Roads and the attempt to save the graffiti, petroglyphs, and markings of the travelers on these ancient routes in the midst of the planned construction "of a dam in Pakistan [that] is threatening some of these petroglyphs." An international team is "working to document them online while there is still time." Finally, Patricia Kim was on the Lesche podcast to discuss Hellenistic queenship.

The New York Times published a number of Barnard faculty letters this week discussing free speech on college campuses. Among the authors is Rome Prize recipient and Pultizer Prize-winning writer Jhumpa Lahiri and thee Elizabeth Castelli, the president of Barnard’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors.

In The Guardian, they report that at the Jordanian world heritage site of Petra, there is a push to transform the site into an even bigger tourist destination. The shift has increased attempts to push out the Bedouin from the Bdoul community from their homes in the 2400-year-old caves near to the archaeological area. They have lived there for about 200 years.

[T]o many of the Bdoul such words mean little. “We have lived here all our lives. Our freedom is being outside,” Feras said. “Here the children have freedom to go out with the sheep and run over the mountain. This is our soil.”

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 129, No. 4 (2025)

Antike und Abendland Vol. 71 (2025)

Classical World Vol. 118, No. 4 (2025) NB Kyle A. Jazwa "Classics and the US Craft Beer Industry"

Greece & Rome Vol. 72, No. 2 (2025)

Journal of Late Antique, Islamic and Byzantine Studies Vol. 4, No. 2 (2025)

Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 28, No. 1 (2025) NB Laura Nasrallah "Centering Cyprus in Late Antiquity"

Analecta Bollandiana Vol 143, No 1 (2025)

Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies Vol. 49, No. 2 (2025)

Byzantinische Zeitschrift Vol. 118, No. 3 (2025)

Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association Vol. 20, No. 2 (2024)

Erudition and the Republic of Letters Vol. 10, No. 3 (2025)

Ancient Philosophy Today Vol. 7, No. 2 (2025) Ancient Philosophy and the Ethics of Belief

Epoché Vol. 30, No. 1 (2025)

Accessible German New Testament Scholarship (AGNTS) Vol. 1, No.1 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions Vol. 25, No. 1 (2025)

Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus Vol. 23, No. 2-3 (2025) They Suffered Under Pontius Pilate: Jewish Anti-Roman Resistance and the Crosses at Golgotha

Judaïsme Ancien = Ancient Judaism Vol. 12 (2024)

Proche-Orient Chrétien Vol. 75, No. 1 (2025) Jubilés d’Espérance

Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 79, No. 4 (2025)

Journal of Semitic Studies Vol. 70, No. 2 (2025) NB Ahmad Al-Jallad "Ancient Allah: An Epigraphic Reconstruction"

Advances in Archaeological Practice Vol. 13, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Social Archaeology Vol. 25, No. 3 (2025)

In Memoriam: Michael C. J. Putnam by Joy Connolly

Michael C. J. Putnam passed away in August at the age of 91. Michael lived a long and full life, but his loss is wrenching nonetheless.

Let me venture to say that I’m well placed to commemorate Michael precisely because I am not his student, colleague, or co-editor. This was one of Michael’s gifts: the extraordinary generosity that he offered to me and to many others who were not in his closest circles. Reader of drafts and provider of reliable advice, he loved lively conversation on a thousand themes, from classical music and New England botany to travel in his beloved Italy. His mischievous laughter and tales of the delights and follies of scholarly life enlivened many a conference.

Michael’s achievements as a scholar, particularly of Vergil and other Latin poets, will endure in his many essays and books. My own favorites are Vergil’s Pastoral Art (1970), a learned, lucid introduction to Vergil’s ten Eclogues, and The Humanness of Heroes (2011), a collection of essays about the end of Vergil’s Aeneid. Separated by forty years, they display the best of humanist philology: a keen attentiveness to the distinctive ways that reading can help sharpen moral and intellectual capacities – if not of judgment, at least of observation and reflection. “To Putnam,” I wrote in a review of The Humanness of Heroes, “Aeneas’ failure to master his passions on the battlefield from books 10-12 makes him not a moral exemplum (far from it) but a reminder to Augustus, and to us today, that in an important sense [like Aeneas at the end of the Aeneid] we are always standing before our own kneeling suppliants. ‘From clinical outsiders,’ Putnam observes, ‘we ourselves have evolved, through Vergil’s magic, into participants in enduring the actuality of suffering.’” This is critical scholarship that does not demand acquiescence to the claim “my reading is correct,” but invites thoughtful engagement and dialogue, like the poems he loved to study and teach.

Immersed as he was in Latin literature and the European genres it helped spawn, Michael was not a reflexive defender of canons. While he worried about the drift to presentism and erosion of language skills he saw over the years, I never heard him weaponize that worry. In his teaching and editing, he encouraged scholarship that drew deeply on political theory, anthropology, and the like.

Great scholarship needs strong infrastructure, and Michael used his skills with people, organization, and fundraising to strengthen a long list of organizations. Along with the American Academy in Rome, he served the Center for Hellenic Studies as Acting Director; he was president of the American Philological Association, a delegate to my own organization, the American Council of Learned Societies, and an active member of boards inside and outside academia.

One of my fondest memories of Michael is a brief impromptu foxtrot we enjoyed during the cocktail hour at a gala in New York City for the American Academy in Rome. His eminence as past Mellon Professor in Charge and as Trustee and Life Trustee of the Academy, not to mention his many awards, never got in the way of his spontaneous expressions of delight in the company of others or his willingness to help the younger and less experienced with introductions and words of encouragement.

A brilliant reader, an eloquent writer and teacher, a major presence at Brown University and in the field of classical studies for many decades, and owner of a joyful laugh, Michael Putnam was an inspiration to many. May we all continue to carry on in Michael’s spirit.

Workshops, Lectures, and Exhibitions

Ancient Exchanges in a Global Antiquity: CFP: Association of Ancient Historians Meeting 2026: Iowa City The 2026 AAH Annual Meeting will take place in person at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, IA from April 16-18, 2026. We invite abstracts for papers of 15-20 minutes in length. Please submit anonymous abstracts for one of the panels below of no more than 500 words to the AAH 2026 Form. The deadline for abstract submission is December 1, 2025. Additional information may be found at aah.conference.uiowa.edu. Please direct any inquiries to the conference organizers at Sarah-Bond@uiowa.edu . Keynote Speakers: Michael Kulikowski (History and Classics, Penn State University), Carolina López-Ruiz (Classics, University of Chicago).

At ISAW's Expanding the Ancient World online workshops for K-12 teachers and beyond, there are a number of upcoming events. On September 29, 2025 at 5:30 pm ET, Leopoldo Fox-Zampiccoli discusses "To Be, To Believe, To Do, and Not To Do: How to Talk About Ancient and Modern Religion(s) with Students" on Zoom. And on October 22, 2025, Kimiko Adler will discuss "Foreign Cults in Imperial Rome: Long Since Has the Syrian Orontes Flowed into the Tiber." Sign up!

On October 18, from 2–3:30 pm EST / 11 am–12:30 pm PST, join the AAACC for a discussion with Thu Truong on her article “Ocean Vuong, Intertextuality, and the Limits of Interpretation,” which was awarded the prestigious John J. Winkler Prize in 2025. Register here.

At the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, Lawrence M. Berman will discuss "Mavericks: Three Visionary Pharaohs of Egypt," on October 15, 2025, 6:00PM - 7:00PM ET. Advance registration recommended for online and in-person attendance.