Pasts Imperfect 8.14.25

This week, Mellon Leadership Fellow and Nero scholar Lauren Donovan Ginsberg busts the myth of the useless humanist. Then, new ancient world scholarship, new journal issues for a global antiquity, upcoming workshops and much more.

This week, Mellon Leadership Fellow and Nero scholar Lauren Donovan Ginsberg busts the myth of the useless humanist; a falsehood often used to justify cuts to humanities departments and programs today. Then, we make the switch from Substack to Ghost (because Nazis), a new book on ancient Mediterranean incarceration goes open access while another looks at ancient magic and heresy, Anthony Grafton reviews two worthy tomes on the Renaissance library (and medieval rules against cheese in them), a new study finds potatoes came from tomatoes, a Black Death study guide for your next premodern plagues course, the Piprahwa Gems are repatriated to India before their scheduled auction, new ancient world journals, and much more.

The Myth of the Useless Humanist by Lauren Donovan Ginsberg

“Departments that don’t pull their weight need to be trimmed so we can preserve our larger academic mission. We wouldn’t do this if we didn’t have to.”

How many of us have heard some form of this from one of our university leaders?

How about this one: “Students need a practical major that gets them a job. There aren’t jobs for lit majors out there.”

Statements like these took hold of higher-ed discourse in the wake of the 2008 economic crash and positioned the humanities as luxuries we can’t afford. They rest on two assumptions that are demonstrably false. First, that the humanities are a drag on university budgets and must be propped up by profitable (read: STEM) units. Second, that humanities students don’t have good job outcomes. I deeply believe that the value of the humanities (and college degrees as a whole) go far beyond the desire to view education only in terms of return on investment (ROI), but I’m tired of hearing people inside and outside universities repeat falsehoods as facts.

I’ll start with the first. The assumption that grant funding means larger ROI for a university has fueled many “strategic realignment” plans and “concerns over the opportunity costs” of supporting the humanities. It’s true that when we compare NSF and NIH research funding, the NEH accounts for 0.015% of federal investment in research. But that doesn’t mean that humanities programs don’t “pull their weight.” Higher ed’s focus on grant funding in budget discussions ignores money earned through our primary mission: teaching students. Studies comparing workload-based revenues to unit expenditures repeatedly show that we bring in more than we cost. Our salaries are lower, the cost of our internationally recognized research is negligible to the institution, our space needs are low, and we teach more classes per year. And while students pay the same amount to study engineering or literature, humanities courses are significantly cheaper to run than STEM courses (aside from math – go math!).

If the enrollment money we bring in surpasses our costs, what happens to that surplus? Well, it’s never really considered surplus because tuition is centrally collected and distributed according to the university’s budget model. Tuition pays for a lot of student-facing services that are non-instructional like advising, counseling and psychological services (CAPs), programming, etc., so units don’t see all the funds they bring in come back to them. But the funds which departments get on the back end are usually not even close to proportional to what they brought in: to quote Christopher Newfield, a professor of literature and former president of the Modern Language Association who has been studying this for decades:

“some departments get more instructional revenue than what they earn through their teaching, some get less… engineering received twice the instructional revenues that it earned through its teaching workload. Arts and humanities got less than half.”

Far from draining the system, humanities programs indirectly subsidize STEM programs.

This isn’t new information. In a 2009 NYT article about rising tuition, Jane Wellman, then the executive director of the Delta Project on Postsecondary Education Costs, Productivity, and Accountability, noted that English department revenue often financially supports STEM departments. In a follow up email, she suggested that “cutting humanities is penny-wise and pound-foolish. … Even though scientists bring in research money, research grants never pay their full costs, so they actually erode resources from the general instructional program. Cutting budgets further in the courses that are already the lowest cost is nutty.” If budget cuts are really about “departments that don’t pull their weight,” shouldn’t the humanities be cut last?

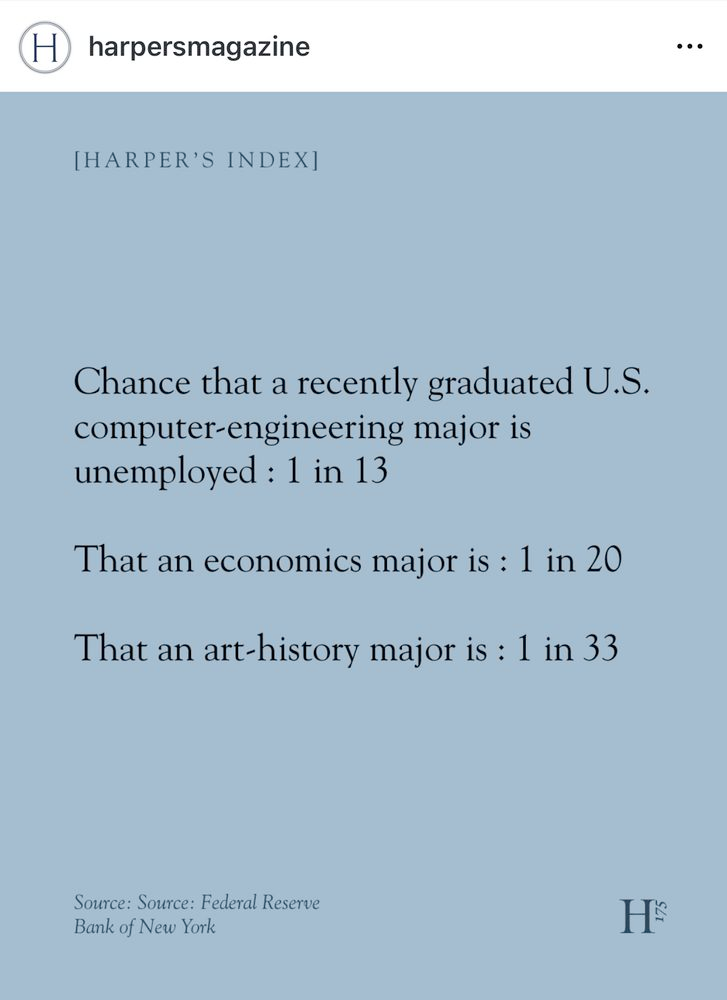

Time for the second falsehood. We have long had data to debunk the idea that STEM degrees produce better job prospects. Recent data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York show that those who major in philosophy, art history, or languages are less likely to face unemployment than majors in, for example, computer engineering, physics, chemistry, or computer science. Humanists also tend to be happier with their jobs. Want to talk salaries? While initially humanists may make less, in the long run humanities students keep pace with or outpace degree holders in so-called “professional” subjects where pay increases often flatten in the first decade of employment. A much lauded survey of 318 major US employers indicated overwhelmingly (93%) that field-specific knowledge was less important than broad humanistic competencies. A self-study done by Google showed that among the qualities defining Google’s top employees, STEM expertise was last. Another revealed that the company’s most important new ideas had come from “B-Teams” comprised of employees who have all those humanistic skills.

AI is also shifting the landscape in favor of humanists. Google, IBM, Goldman Sachs, and the COO of Blackrock have all stated a desire to hire “people who majored in history, in English, and things that have nothing to do with finance or technology” — some to support their own AI endeavors, others because they recognize that AI is currently least able to replace humanistic skills and is unlikely to get there. When I posted some of these statements on BlueSky, other employers across finance, tech, law, cybersecurity, and other fields replied that they too want to hire humanists. Medical schools agree – they’re looking for candidates with intercultural awareness and humility, ethics training, empathy and compassion, critical thinking, and other humanistic skills. We often hear that healthcare is a good bet for employment, but rarely cited in the same breath is that the health sciences have overwhelmingly embraced the humanities as a core part of desired undergraduate training. John McGowan, former director of UNC’s Institute for the Arts & Humanities, has shown how disingenuous it is to separate those two things.

While the last decade has seen some states, including my own, consider charging humanities students more in tuition (see sociologist Daniel Lee Kleinman’s chapter in New Deal ), the various pieces I cite throughout this essay have shown that industry leaders back up what we see in outcomes data: humanities students emerge with a flexible set of skills and capacities that keep them very employable. Cutting the humanities may even make it harder for our students to develop these marketable skills. If what we care about is job outcomes, isn’t that enough to sound the alarm? If our universities continue to tell students (and their parents) that they can best position students for challenging job markets, they should be promoting the humanities.

Recently the Mellon Foundation has called attention to how few humanists hold upper administrative positions at R1 institutions. This, they recognize, is part of the reason the humanities have become so vulnerable in the era of “budget realignment.” I was lucky to be a fellow in one of their funded leadership training programs and over the course of two-years have seen enough data to know that these false narratives do not exist solely outside the academy but are also promoted inside our own house. Our leaders treat them as obvious truths and make decisions based on them. We need to share with them and others the data that challenges those assumptions. And when speaking to those who know this data and cut us first anyway, we need to call a spade a spade: cutting us is ideological, not financial. If our universities’ primary fiduciary responsibility is to the education we provide our students, the humanities should be one of the things growing in times of austerity. Why isn’t this the case?

Public Scholarship and a Global Antiquity

We admit it: we ghosted you. If you are reading this newsletter, note that we have migrated over to our newsletter on the open platform Ghost. As PI co-founder Joel Christensen wrote about on Sententiae Antiquae, Substack has been platforming and pushing Nazi newsletters. We thought it was time for a change. Here is our new web address.

In The Chicago Maroon, Clifford Ando has an important op-ed, "Reorg 101: The Past and Future of the Race to the Bottom." In it, he looks at the University of Chicago and the "working groups" tasked with reforming the arts and humanities departments there. Much of what he says mirrors what Ginsberg notes above.

As regards the reform and reorganization of the Division of the Arts and Humanities, what we appear to have is a plan in search of a rationale; we’re going to disrupt and then see what happens; we don’t even know whether we will achieve the efficiencies that are the reform’s stated goals, let alone what their effects on academic excellence and institutional reputation will be. We will simply fracture the homeomorphy between pedagogy, local institutional life, and national and international disciplinary organizations that has long sustained us and hope for the best.

And yesterday, Ando wrote to the Liverpool listserv to say that "the Dean of Humanities at the University of Chicago is 'pausing' graduate admissions in all departments that require language study (except, it appears, Chinese)." This is an incredibly sad development.

On Tuesday, Matthew D.C. Larsen and Mark Letteney published their much anticipated book, Ancient Mediterranean Incarceration. It is open access from the University of California Press. As they note, "This book examines the spaces, practices, and ideologies of incarceration in the ancient Mediterranean world, covering the period from 300 BCE to 600 CE." Renowned artist Titus Kaphar and the Gagosian Gallery worked directly with the authors so that they could feature one of his icons from the "Jerome Project" (2014-2015) on the cover. This isn't the first time that Kaphar has crossed over into the realm of antiquity. In Laura Nasrallah's, Ancient Christians and the Power of Curses: Magic, Aesthetics, and Justice (2024), she discusses his "To Be Sold," which depicts former Princeton University president Samuel Finley (1761–66) as "partially obscured by shredded, hanging canvas strips affixed with nails," with the ancient act of nailing curses.

In the London Review of Books (LRB), Renaissance historian Anthony Grafton discusses two new books, Andrew Hui's The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries and Seth Kimmel's The Librarian's Atlas: The Shape of Knowledge in Early Modern Spain. The review is a fascinating look at information science in the Renaissance, but we simply could not abide by bibliophile Richard de Bury's (1287-1345) belief that students must be kept from library books, "since they ate cheese while they read and dribbled fragments onto the page." The new issue of LRB also has ancient historian Josephine Quinn reviewing Paul Kosmin's The Ancient Shore.

Over at Hyperallergic, our Sarah E. Bond wrote about another man who is ridiculous: specifically, why Mr. Musk really, really needs Greco-Roman antiquity to be straight. If you are going to cite the Sacred Band of Thebes, you better note what held them together.

Early Christianity scholar and ancient magic virtuosa, Shaily Shashikant Patel, has a new book out on Magic and Heresy in Ancient Christian Literature. Historian of premodern medicine and disease, Monica Green, has a forthcoming open-access, introductory teaching module on the Black Death: The Black Death: The Medieval Plague Pandemic through the Eyes of Ibn Battuta, an online course module for the History for the 21st Century (H21) Project. Finally, Roman law expert Zachary Herz just welcomed the publication of his new book, The God and the Bureaucrat: Roman Law, Imperial Sovereignty, and Other Stories, T. H. M. Gellar-Goad has a new translation of Catullus 4, and T.J. Tallie has been working hard in the Lambda archives to uncover LGBTQ+ history in San Diego.

People, if you needed another reason for fear/respect of the ocean, this story will do it. Ocean currents shifted the sediment on an Oahu beach near a US Army recreation center to expose anthropomorphic petroglyphs. Army archaeologists believe that they are over one thousand years old. An Army official made sure to note that, while the glyphs are visible now, the ocean will invariably cover them up again. She giveth! She taketh away!

The current conditions in Gaza are horrendous. And as reporters at The New Arab discuss, archaeology continues to be used as a tool of colonialism on the West Bank: "Residents of Sebastia, northwest of Nablus, have sounded the alarm after an Israeli military order declared nearly 40 percent of the town's lands as an 'Israeli archaeological area.'" The latest actions follow a long pattern.

If you're anything like this PI editor, you're sprinting to the nearest farmer's market ("far-mar," in our household parlance) to take full advantage of fresh summer produce. And if you're even more similar to this editor, you will love the potato-based puns in Javier Barbuzano's piece titled "Potatoes have their roots in ancient tomatoes." Their genomes are ... mashed-up! (I know that I, Sarah, will be blamed for this pun, but this was actually the witty brilliance of Stephanie).

Over at the New York Times, breaking news reporter Claire Moses reports on the Piprahwa Gems, Buddhist relics that were taken from a village in northern India by a British dude in 1898. They have now been repatriated and will soon rejoin their fellow relics at the Indian Museum in Kolkata.

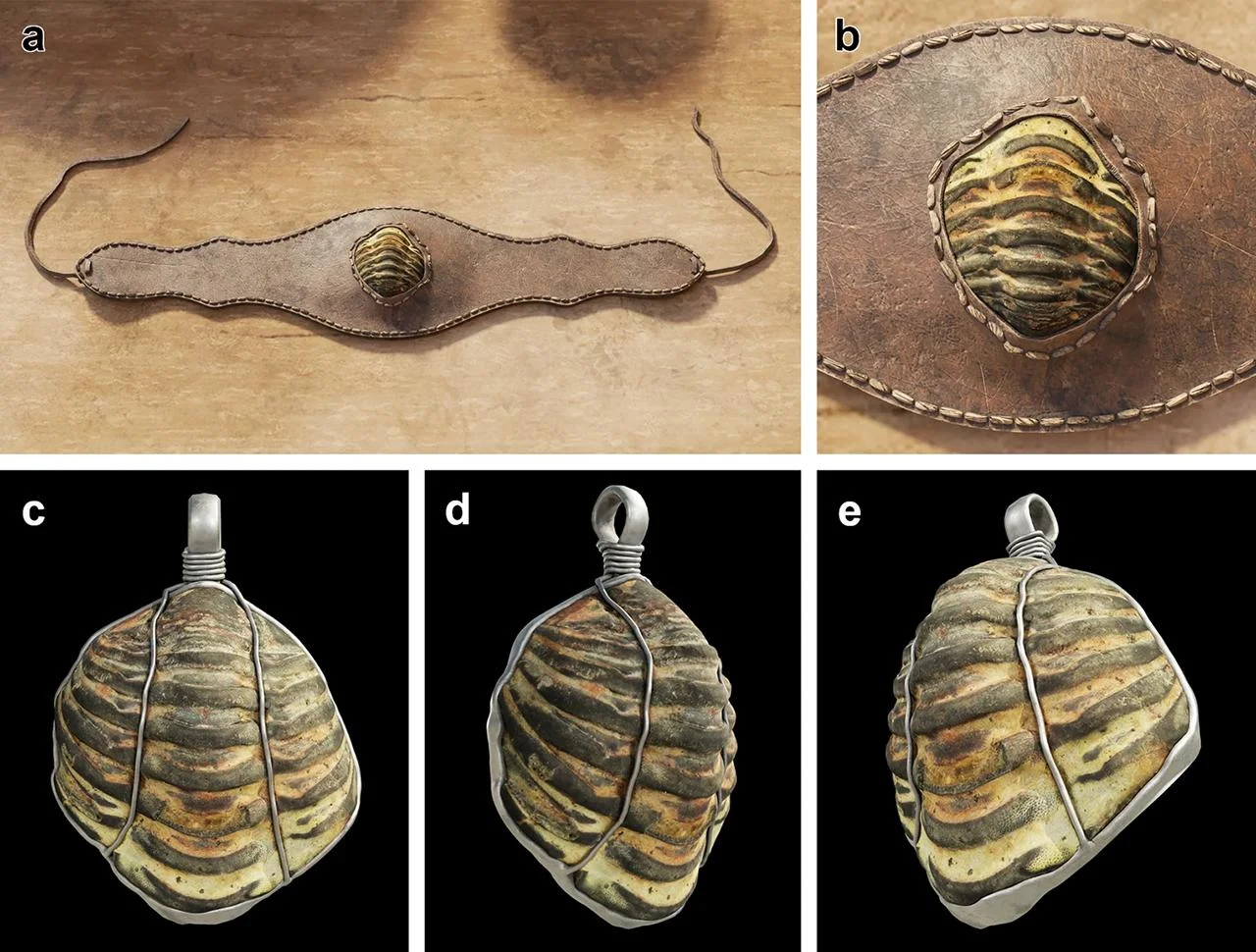

Lest you think that the Greco-Roman world was all war, doom, and gloom, don't forget that the ancients needed bling too: in the form of trilobites, as was the case in what is now Spain. If you liked it, then you should have put a fossil on it, etc.

At Science, they cover a new article published in Antiquity studying an early medieval cemetery at Updown in Kent, England. The authors found a young girl from around 650 CE with West African origins. “Her paternal grandfather was 100% West African,” said Stephan Schiffels, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who also co-authored the new DNA analyses. Another individual at Worth Matravers, Dorset, also had "recent ancestors in sub-Saharan West Africa."

And, finally: 10 points if you can figure this one out. Why are these ancient Roman shoes so big?? 🥾

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Anales de Historia Antigua, Medieval y Moderna Vol. 59 No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Anzeiger für die Altertumswissenschaft Vol. 88, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Arion Vol. 33, No. 1 (2025)

Ciceroniana On Line Vol. 9 No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Classical Receptions Journal Vol. 17, No. 3 (2025)

Frammenti sulla Scena (online) Vol. 5 (2024) #openaccess

Hermes Vol. 153, No. 3 (2025)

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 12 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Latomus Vol. 84, No. 1 (2025)

Nova Tellus Vol. 43 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Ordia Prima Vol. 3 (2025) #openaccess

Palamedes Vol. 15 (2023/4) Studies in Honour of Adam Ziółkowski

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 9, No. 3 (2025) The Ways that Never Parted: A Roundtable & more

Synthesis Vol. 32 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess Del treno al epitafio: el lamento funeral en la antigua Grecia y sus inflexiones

Trends in Classics Vol. 17, No.1 (2025) Diagnosis: Late Antique Taxonomies in Medicine and Healing

Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia Vol. 31, No. 1 (2025)

IRAQ Vol. 86 (2024) NB Jill Goulder "The Uruk bevel-rim bowl: new insights on technology, multi-function and dispersal"

Journal of Cuneiform Studies Vol. 77 (2025)

Le Muséon Vol. 138, Nos. 1-2 (2025)

Studia Iranica Vol. 52, Fasc. 2 (2023)

Apocrypha Vol. 34 (2025)

Cahiers d’études du religieux. Recherches interdisciplinaires Vol. 27 (2025) Gouverner les âmes et les corps

Collectanea Christiana Orientalia Vol. 22 (2025) #openaccess

Frontières Suppl. 3 (2025) #openaccess Le christianisme aux frontières

Journal for the Study of Judaism Vol. 56, No. 3 (2025)

Journal for the Study of the New Testament Vol. 47, No. 5 (2025) Booklist

Revue d'Etudes Augustiniennes et Patristiques Vol. 70, No. 2 (2024)

Bulletin of the John Rylands Library Vol. 101 , No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

The Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures Vol. 51, No. 2 (2025)

Manuscript Studies Vol. 10, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess NB Maddalena Poli, "Confucius and the Richness of Ancient Chinese Manuscripts"

Parekbolai Suppl Vol 1. (2025) #openaccess

Aldrovandiana. Historical Studies in Natural History Vol. 4 No. 1 (2025) #openaccess Studies on Ancient Plants. Multidisciplinary Approaches and New Perspectives

Ancient Philosophy Vol. 45, No. 2 (2025) NB Caterina Pellò "Why We Sleep?: Early Greek Theories of Sleeping and Waking"

Bochumer Philosophisches Jahrbuch fur Antike und Mittelalter Vol. 26, No. 1 (2023)

Comparative Philosophy Vol. 16, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess NB John R. Shook "A Place for Ancient Philosophy in Axial Age Historiography"

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 86, No. 3 (2025)

Philosophy East and West Vol. 75, No. 3 (2025) The Life and Work of J.N. Mohanty: A Philosophical Tribute

Medicina nei Secoli: Journal of History of Medicine and Medical Humanities Vol. 37 No. 2 (2025) #openacces

Advances in Archaeological Practice Vol. 13 (2025) #openaccess Caring for Culture in the 21st Century

Antiquity Vol. 99, No. 406 (2025)

Cambridge Archaeological Journal Vol. 35, No. 3 (2025) #openaccess NB Christian Langer & Kexin Zhao. “The Nile and the Yellow River: Comparative Studies between Ancient Egypt and China”

Gallia Préhistoire Vol. 65 (2025)

Journal of Urban Archaeology Vol. 11 (2025) Archaeological Perspectives on Urban Sustainability

Open Archaeology Vol. 11, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Zeitschrift für archäologische Aufklärung Vol. 2, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Workshops, Lectures, and Exhibitions

On May 17, 2025, "Kingship and Power in Assyria" opened at the SAMA in San Antonio, TX. "Through a partnership with the Art Institute of Chicago, SAMA has a special opportunity to display an ancient relief sculpture from the palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, in present-day Iraq." And beginning on September 27, 2025, the Walters Art Museum has "Soulful Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt." The exhibition goes until January 11, 2026.

Making the Medieval Archive, a day long symposium on September 12, 2025 at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries and online, will commemorate the legacy of medieval historian Elizabeth (Peggy) A. R. Brown (1832-2024) and mark the establishment of the Elizabeth A. R. Brown Medieval Historians’ Archive, a dedicated repository for the professional papers of medievalists.

On Saturday, September 13, 2025, at 1pm (eastern US time) on Zoom, the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) is hosting a lecture from Geoff Emberling to discuss "New Light on Ancient Napata: Urban Center of the Empire of Kush." Register here.