Pasts Imperfect (2.19.26)

This week, classicist Curtis Dozier discusses new books—including his own—that critique Classics and the ways it is instrumentalized. Then, the role of Blackness in the imagery of the Middle Ages, an important new Edmonia Lewis retrospective, repatriating the Benin Bronzes, the pre-Inca Chincha Kingdom's use of bird guano as fertilizer, a symposium on caring for African cultural heritage, celebrating the Lunar New Year 🐎 and Ramadan, new ancient world journals, and much more.

Classics and the White Pedestal by Curtis Dozier

It is now almost ten years since a mob in Charlottesville, Virginia chanted "Jews will not replace us." And it is five years since rioters at the United States Capitol hung a noose on the mall and flew Confederate flags inside the halls of Congress, making it all but impossible to view the movement that revealed itself at Charlottesville as a fringe phenomenon. And as the current administration continues to rewrite history to erase the long history of white supremacy in the United States while targeting immigrants and citizens alike for violence and even murder, it should be clear to all that the hateful ideologies that fuelled the Charlottesville rally and the Capitol attack are not just politically ascendant, but triumphant.

Symbols and slogans drawn from Greco-Roman antiquity were omnipresent throughout the rise of this movement. As the liberation archaeologist Lyra Monteiro argued concerning the display of many symbols and slogans from Classical antiquity by January 6th rioters and the neoclassical backdrop of the riot itself, Greco-Roman antiquity was one of the threads that linked the Charlottesville rally to the attempt to prevent the peaceful transfer of presidential power.

Now, such invocations have moved from the so-called radical right into the mainstream of American politics. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson has claimed that homosexuality destroyed the Roman Empire. White House advisor Stephen Miller has claimed an ancestral link between members of his political movement and antiquity, boasting that "our lineage and our legacy hails back to Athens, to Rome." And the most authoritarian president the United States has seen in generations has bulldozed a third of the White House in order to make way for a new wing designed to look like an ancient Greek temple.

These references to Greco-Roman antiquity all share an appeal to the sophistication and prestige that many people associate with ancient Greece and Rome. This rhetorical move is the recurring theme of my new book, The White Pedestal, in which I examine how white nationalist activists attempt to harness the prestige of "the Classical" to make their hateful and violent ideology appear respectable, desirable, and even inevitable.

On the one hand this appeal to authority is almost laughable: it boils down to the logical fallacy of claiming that because an admired ancient person like Plato, for example, advocated eugenics, that means eugenics must be a good idea. But as I argue in my book, this fallacious logic characterizes the way that some of the most admired and influential intellectuals and historians in history — not just "extremist" or "fringe" thinkers but those central to Anglo-European intellectual history — have used ancient history, more often than not to legitimize racist pseudo-science and violent colonialism. And from the vantage point of 2026, it is clear that such claims of legitimacy — however fallacious — work.

My book is only one contribution to an ever-growing body of work exposing and interrogating the myriad ways that "the classical" can and has been used to promote violent and oppressive politics. As a complement to and significant expansion of my book's focus on the contemporary United States, we can look forward to the forthcoming volume Abusing Antiquity? Classics and the Contemporary Far Right, edited by Denise McCoskey and Helen Roche, which offers a global perspective on this phenomenon. But as I hope to have shown in The White Pedestal, so-called "extremism" is only a symptom of the entanglements of popular and mainstream academic classicism in white supremacy.

These entanglements are a major theme of Dan-El Padilla Peralta's Classicism and Other Phobias, but the documentation of the multifarious operations of what he terms "overrepresented classicism" is only one dimension of this project. Padilla Peralta also challenges us to recognize modes of classicism, including those that may not incorporate anything straightforwardly connected to ancient Greece or Rome, that can serve not as mere alternatives to white supremacist classicism but as tools to eradicate it.

This turn to heretofore unrecognized concepts of classicism also characterizes a recent book by Padilla Peralta's collaborator Sasha-Mae Eccleston, Epic Events: Classics and the Politics of Time in the United States Since 9/11. Beginning with what is surely the best analysis yet of the inclusion of an Aeneid quote in the 9/11 Memorial, Eccleston builds to a far-reaching exploration of how dominant power "classicizes" historical events, whether from Greco-Roman antiquity or the much more recent past, imbuing them with a timelessness and universality that elides the violence such (a)historical narratives of universality enact. Interested readers can gain historical perspective on the dynamics of classicism's exclusions in the narratives that are now available in the open access volume edited by Sarah Derbew, Daniel Orrells, and Phiroze Vasunia, Classics and Race: A Historical Reader, beginning perhaps with the "Reminiscences of School Life" by Fanny Jackson Coppin and the accompanying essay by Shelley Haley.

Two forthcoming books offer sustained treatments of issues related to a further claim I make in The White Pedestal: that the authentic remains of Greco-Roman antiquity, without distortion or "abuse," positively invite appropriation by racist, xenophobic, misogynist, and homophobic actors. The Cambridge Companion to Classics and Race, edited by Rosa Andújar, Elena Giusti, and Jackie Murray and due to be published this spring, revises and even overturns the dominant orthodoxy that "race" and "racism" can only anachronistically be applied to the ancient world. Rebecca Futo Kennedy, one of the contributors to that volume, will offer a book-length reframing of scholarship on ancient concepts of identity, ancestry, and human difference in a forthcoming monograph.

But how do we move forward as a field? We can look toward the work of Kelly Nguyen, which provides one model for how we can put into practice these critiques of classicism. In addition to award-winning scholarship on classicism in colonial Vietnam and the post-colonial diaspora, Nguyen leads a team that has built a database to preserve the experiences of Vietnamese refugees. Taking up, in a sense, Padilla Peralta's and Eccleston's challenge to scholars to disassociate classicism from Greco-Roman antiquity, the experiences in Nguyen's database may or may not bear traces of the "Classical," conventionally defined. But dignifying and preserving these stories of displacement and resilience — making them, as it were, "classical" — reimagines a classicism that has the potential to shatter its bonds with white supremacy.

I will not declare 2026 a golden age of anything. But we are nevertheless fortunate to have these resources to show us how to challenge the ways of valuing ancient Greece and Rome that have contributed to our present moment and to imagine a better future.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

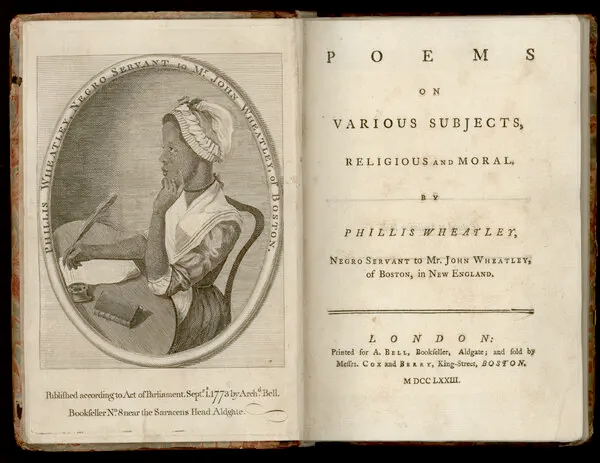

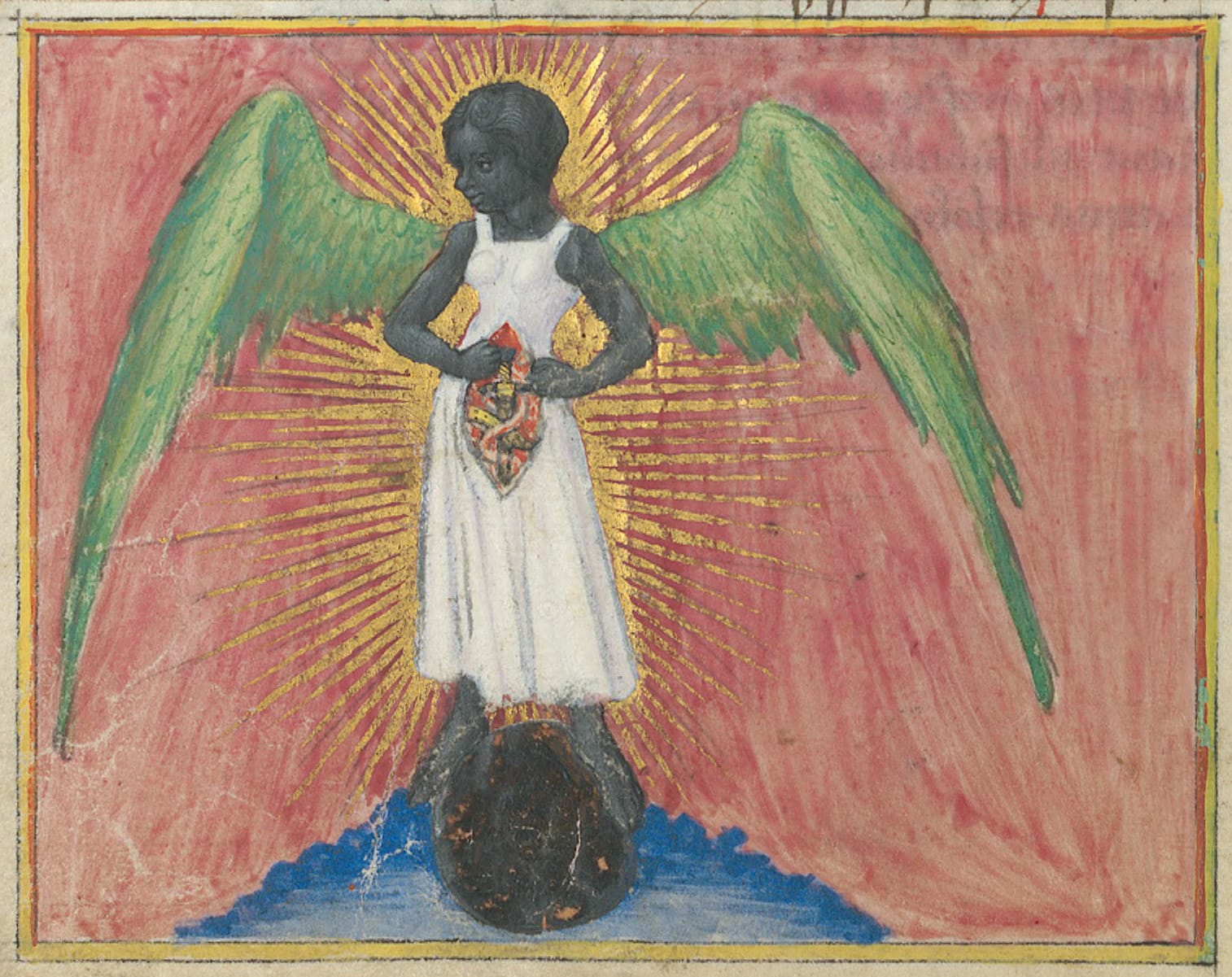

In Hyperallergic, art historian Denva Gallant has a touching essay that underscores how "medieval culture offers a way of thinking about love that still speaks to the present."Gallant explores the role of Blackness in the imagery of the Middle Ages, and offers an important way of parsing these works: "Blackness here becomes visible on the body’s most exposed surface, rendering nigredo not as abstraction but as something shared, embodied, and recognizably human. It was this move — blackness understood as an enduring, human condition rather than a symbolic overlay." The essay was partly based on a lecture given at the Love: A RaceB4Race Symposium.

At Forbes, arts reporter Chadd Scott covers the stunning new exhibition that opened on February 14, 2026 (i.e., Douglass Day), at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA. It is the first major retrospective for the Black and Indigenous (Mississauga) sculptor Edmonia Lewis.

Her initial artistic successes came from creating small portrait medallions of famous American abolitionists, artworks popular during the Civil War. After moving to Rome, she continued her commitment to the antislavery cause with works like Forever Free, the first sculpture by a Black artist in the United States to celebrate emancipation.

You may also know her from her epic "The Death of Cleopatra" (1876) or her "Young Octavian" (1873). You can read art historian Harry Henderson's epic biography of Edmonia Lewis for free at the Internet Archive.

Let's discuss museums. The Museums Association announced that "The University of Cambridge has handed over the legal title of 116 Benin bronzes in its collections to the Nigerian authorities." The move puts necessary pressure on the British Museum to follow suit. In addition, the University of Edinburgh repatriated ancestral remains to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation "more than 150 years after they were taken." And Art & Object discusses the Smithsonian's announcement of the return of "a Shiva Nataraja statue and two other Chola Dynasty bronzes to India from the National Museum of Asian Art under a “shared stewardship” policy introduced in 2022." But is "shared stewardship" really repatriation?

The Conversation reports on recent research by University of Sidney archaeologist Jacob L. Bongers and collaborators that sheds new light on economic activity in Incan and Pre-Incan Peru. Chemical analyses of agricultural and avian remains suggest the trade in guano for fertilizer facilitated the rise of the pre-Inca Chincha Kingdom. Another recent paper by Bongers, et al, provides a potential explanation of the "Band of Holes" at Monte Sierpe in Southern Peru. This strip of precisely aligned holes almost a mile long and over seven-hundred years old has puzzled archaeologists since its discovery in 1931. Bongers and his team used drones to map the site revealing numerical patterns in the arrangement of the holes, while pollen analyses revealed agricultural products were placed in the holes. This new evidence suggests Monte Serpe served as an exchange nexus with a physical accounting system, akin to khippu, the knotted strings used by the Inca as a recording system. As Bongers puts it, “In a sense, Monte Sierpe could have been an ‘Excel spreadsheet’ for the Inca Empire."

Happy Lunar New Year! 🐎 It is the year of the fire horse now. And according to the zodiac, this means an energetic, fast-paced, and spirited year. I (Sarah here!) really enjoyed Dianne Choie's rundown of the history of the holiday for the Library of Congress. Also, I want to go on record that I am totally okay with it being a slow-paced and boring year if the fire horse, you know, 2026 wants to chill on that rapid news cycle.

Megan Campisi and Pen-Pen Chen recount the myths connected to the Chinese zodiac (生肖)

Finally, in addition to our recognition of the Lunar New Year, we want to wish everyone recovering from Mardi Gras a reflective Lenten season and Eid Mubarak to those observing Ramadan. ✨🌙🏮

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Acta Classica Vol. 68 (2025)

Antichthon Vol. 58 (2024) The Spatial Turn and Roman Studies: Theories and Possibilities

Arethusa Vol. 59, No. 1 (2026) #openaccess

Αριάδνη Vol. 31 (2025) #openaccess NB Peter Agócs "Songmakers and Texts in Early Greek Poetry"

Bulletin de correspondance hellénique Vol. 148, No. 1 (2024) #openaccess

Classical Journal Vol. 121, No. 3 (2026)

The Journal of Juristic Papyrology Vol. 55 (2025) #openaccess

Lexis Vol. 43, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Onoba Vol. 13 (2025) #openaccess

Römisches Österreich Vol. 48 (2025) #openaccess

Synthesis Vol. 33 No. 1 (2026) #openaccess

Archai Vol. 35 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research Vol. 43, No. 1 (2026)

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 87, No. 1 (2026) NB Micha Lazarus "The B’rith of Tragedy: Jewish Roots of a Stolen Genre in Early Modern Europe"

Journal of the History of Philosophy Vol. 64,No. 1 (2026) #openaccess

Philosophy East and West Vol. 76, No. 1 (2026)

Phronesis Vol. 71, No. 1 (2026) NB Norah Woodcock "Mules and Other Monsters: Hybridity in Aristotle’s Generation of Animals"

Vivarium Vol. 64, Nos. 1-2 (2026

Journal of Coptic Studies Vol. 27 (2025)

NABU No. 4 (2025) #openaccess

Annual of the Japanese Biblical Institute Vol. 49 (2024) #openaccess

Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Vol. 50, No. 3 (2026)

Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 144, No.4 (2025)

Digital Philology Vol. 14, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess Unlikening Translation: Words, Sounds, Events, Things

Le Moyen Age Vol. 131, No. 2 (2025)

Antiquity Vol. 100, No. 409 (2026)

Cambridge Archaeological Journal Vol. 36, No. 1 (2026) #openaccess Archaeological Identitiscapes: A Semiotic Stance

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society Vol. 91 (2025)

Exhibitions, Workshops, and Lectures

On Saturday, February 21, 2026 from 2pm–3pm PT, Hebd Abd el Gawad will speak on "Whose Egypt? Challenging How Museums Portray Egypt": "For more than a century, museums have framed ancient Egypt as an object of fascination and often disconnected from its current people and cultures. Egyptologist Heba Abd el Gawad examines how the land’s heritage and identity have been shaped into a museum commodity and how this approach is finally being challenged." To attend in person, register here, to watch online via Zoom, register here.

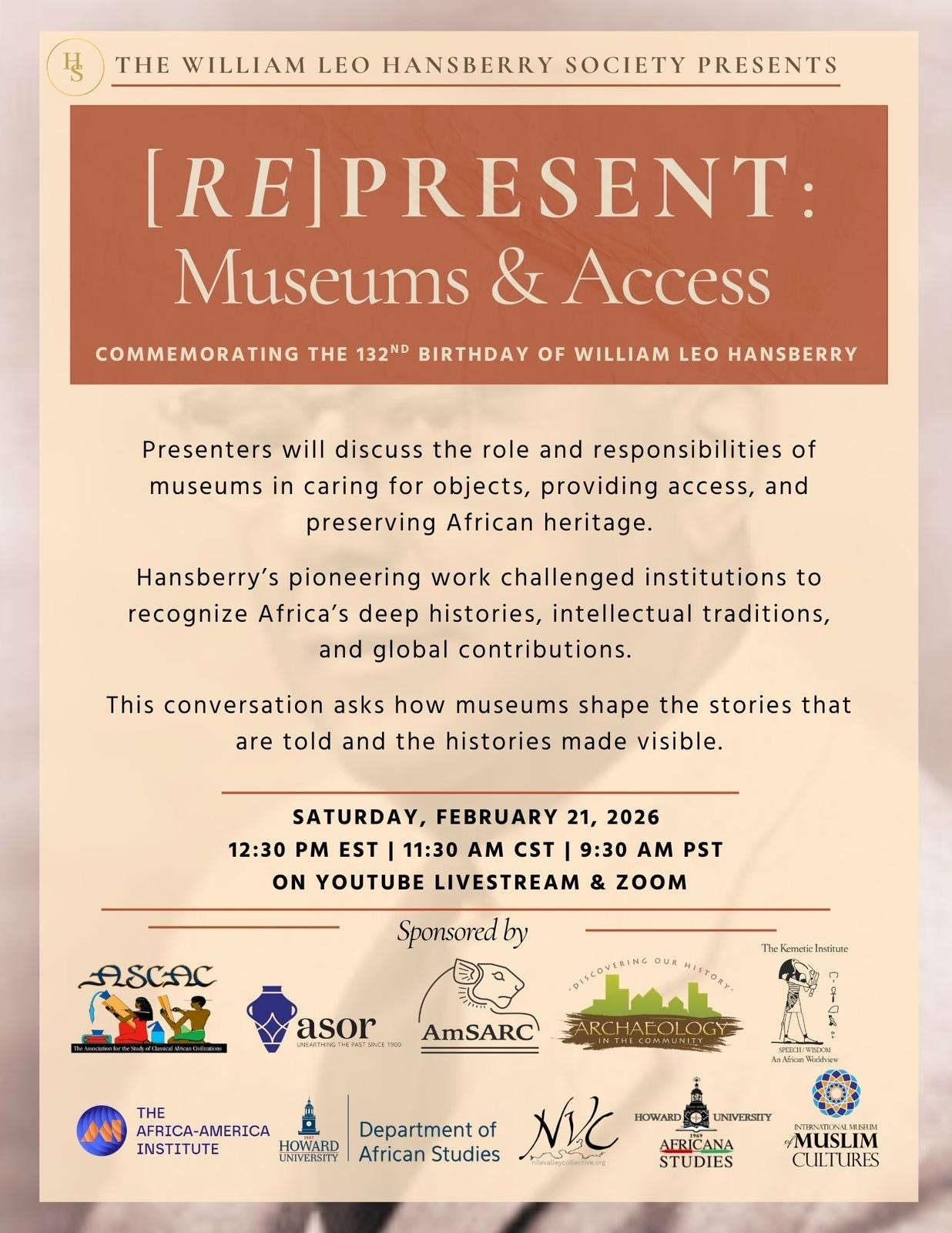

February 21, 2026 is also the William Leo Hansberry Society's Fourth Annual Birthday Commemoration Event: [RE]PRESENT: Museums and Access, which will discuss the the role of museums in caring for African cultural heritage, beginning at 12:30 PM EST | 11:30 AM CST | 9:30 AM PST. There is a Youtube livestream @hansberrysociety or you can register for Zoom here.

Also on Saturday, February 21st, 9am to 2:30pm CT, the John and Penelope Biggs Department of Classics at Washington University in St. Louis will host in person and online: "Digital Paedagogos: A Symposium in Memory of Carl Conrad." Speakers include Helma Dik, University of Chicago, Patrick Burns, Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University, and Jonathan Robie, Biblica, Inc. Please RSVP if you plan to attend in-person, virtually, or would like to share a remembrance.

The Critical Antiquities Network gets its 2026 lecture series underway on February 24, 2026 at 5:30 EST, online and (in person) across the international dateline at the University of Sydney at 9:30am AEDT. Page Dubois will present "Blind Spot: Marxism in U.S. Classics." To receive the Zoom link, please sign up for the Critical Antiquities mailing list here.

On February 28, 2026 at 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM (Canada | Pacific) art historian Sinclair W. Bell will present, "Foreign Faces in Etruscan Art: Ethnicity and Representation in Ancient Italy." Bell will discuss "representations of Black (sub-Saharan) Africans in a variety of visual media, and [explore] what these images may have meant in their original settings." It is live stream only. Please register here for a Zoom link.