Pasts Imperfect (11.6.25)

This week, historian of early Islamic material culture Rhiannon Garth Jones breaks down the reception of Roman antiquity during the Ottoman Empire. Then, dispelling myths about the Black Death; archaeologists discover wampum beads at a 17th century colony in Canada; celebrating Native American Heritage Month; open access books on Aristotle, the Bhagavad Gita, and Global Latin; GIS-mapping the Achaemenid Royal Road, examining ancient Mexican coprolites; new ancient world journals, and much more.

Tracing Ottoman Receptions of Roman Antiquity by Rhiannon Garth Jones

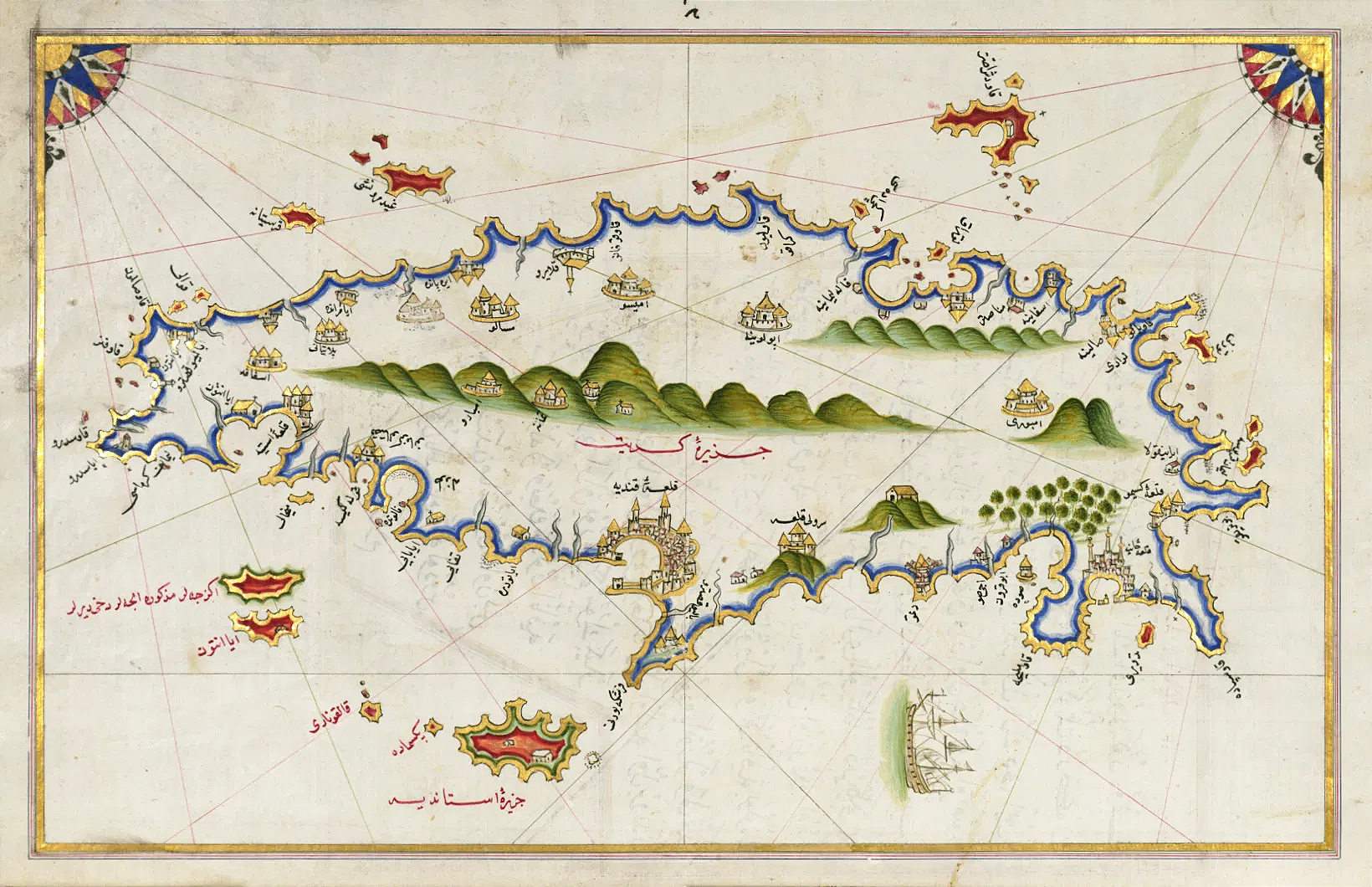

In 1453, after around eight hundred years of trying, a Muslim ruler finally conquered the city of Constantinople – or, as he knew it, Rome. Immediately, he added Kayser-i Rum or ‘Caesar of the Romans’ to his list of titles. This new Caesar sponsored brilliant artists and artisans, built on a monumental scale, promoted scholarship, arranged a trip to what was thought to be Troy to show off his historical knowledge, and ruled an enormous empire with territories across the three continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe. His name was Mehmet II, and we tend to remember him by one of his many other titles: Sultan of the Ottomans.

It feels like barely a week goes by without a major news story invoking Rome. If it’s not a new Roman-style triumphal arch, it’s big tech claiming generative AI could re-write Roman history, or a business magazine taking management tips from the assassination of Caesar. Rome is truly the SEO keyword that keeps giving. Nearly as frequent as these articles are the comments that all this interest in Rome is innocently part of ‘Western Civilisation’ (and, if you want to know more about why this isn’t so innocent, you might start here). We rarely see much coverage of the many ways that successive Muslim empires engaged with Rome – in fact, we find it hard to see this in the historical record at all. Once we start to look, however...

Mehmet II, Sultan of the Ottomans and Kayser-i Rum, ruled in a way that drew on the traditions of ancient Roman emperors, just as many other imperial courts of Europe, West Asia, and North Africa did. He ruled this way because it was how Muslim leaders had always ruled, although he was clearly aware that many of these traditions made him seem impressive in the eyes of his European rivals.

From the earliest days, Muslim rulers from the Umayyad dynasty like Abd a-Malik had built sacred, monumental spaces like the Dome of the Rock in the style of Roman (sometimes called Byzantine) temples and churches. Poets at the court of rulers from the later Abbasid dynasty flattered them with claims that their palaces were better than those of Rome. Fatimid rulers in Cairo rivalled Roman craftwork and jewellery, while Andalusi rulers re-used Roman marble in their architecture and the Aghlabids built mosques drawing partly on Roman traditions to show they were a serious power.

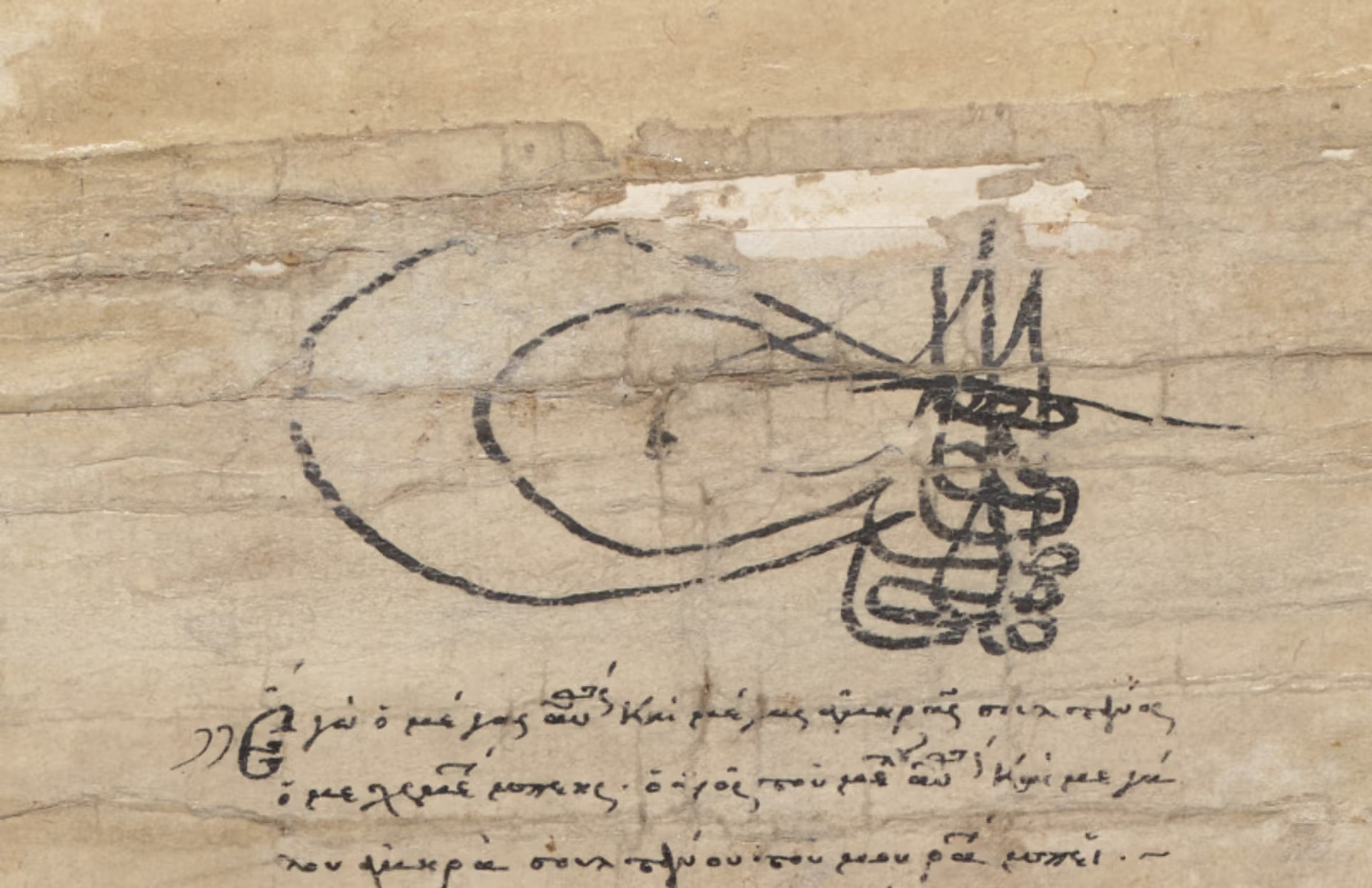

By the time of the Ottomans, many of these elements of Roman rule were well-established in Muslim empires – especially those in academia and architecture. When the Ottomans conquered the city and territory they had always called Rome (or ‘Rum’) and the people living there who they knew as Romans, they expanded this repertoire of Roman references. The most fascinating example comes from perhaps the most famous of the Ottoman rulers, Suleyman I, great-grandson of Mehmet II. As with previous Ottoman Kaysers-i-Rum, his claim and title had been acknowledged by the Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople. Unlike the previous Ottoman rulers, Suleyman seems to have been especially irritated that anyone else might claim the same title so he decided to show the world his Roman credentials – and his superiority to both the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and the Roman Catholic Pope, Clement VII.

At great expense – this is one of the ways that Suleyman became known in Europe as ‘the Magnificent’ – he staged a Roman triumph, a coronation ceremony, and a military campaign all in one. In the year 1532, Suleyman and his armies slowly marched towards the Hungarian territories of Charles’ brother. As envoys from the Holy Roman Empire and other European rulers waited for an audience, Suleyman paraded under purpose-built, classical-style arches while wearing a golden ‘Roman-style’ helmet topped by four-crowns (reports from the time suggest it was similar to the papal tiara but much grander).

The scenes of this Roman triumph and its reception were recreated in beautiful manuscript folios back in Constantinople, as well as in pamphlets, street performances, and poetry for the streets of Europe – meaning more and more audiences could see and judge for themselves who was the real Roman emperor. One of those who judged in favour of Suleyman was the French constitutional scholar and Roman legal expert, Jean Bodin, who noted that, among other things in his favour, Suleyman ruled more formerly Roman territories than Charles.

Suleyman returned from triumph after successfully putting Charles in his place, getting a treaty that included overlordship of the Hungarian territories, and capturing several ancient Roman statues that he apparently planned to display on the monumental columns by the ancient Roman Hippodrome, just as Constantine had once done. At this point, the title Caesar of Rome became less useful to him. His magnificent helmet-crown seems to have been melted down and the statues quietly put away. The Kayser-i-Rum focused on his other titles and his other audiences.

This was not the end of Roman reception in the Ottoman empire, by either the rulers or the ruled. At any period of Ottoman rule, traces of Rome could be glimpsed – varying depending on the time and needs of the different communities. From fountains to mythology, language to religion, these different glimpses reflect the full range of ancient Roman identity. The Ottomans, like so many Muslim empires before them, saw Rome in full colour – something we still struggle to do.

Rhiannon Garth Jones is a historian who works with both material culture and textual sources, with a PhD on the early Abbasid visual language of power and their relationship with Rome during the eighth and ninth centuries CE (second and third centuries AH). She teaches Global Medieval History at the University of Leeds and is the author of the new book All Roads Lead to Rome: Why we think of the Roman Empire daily.

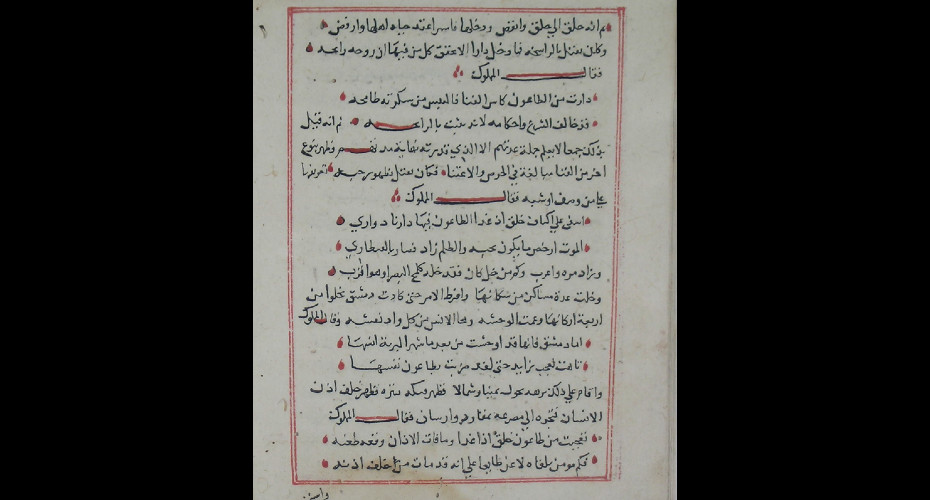

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

How do we dispel the myths surrounding the Black Death? A new study in the Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies by Muhammed Omar, a PhD candidate in Arab and Islamic Studies, and Nahyan Fancy, a historian of Islamic medicine at the University of Exeter, argues that Mamluk Maqāmas on the Black Death "began to be taken as fact by 15th century Arab historians and subsequent European historians." The study questions the Quick Transit Theory of the Black Death by noting that "a literal reading of Risālat al-nabaʾʿan al-wabāʾ by the Mamluk writer Ibn al-Wardī, which literary scholars have long classified as a maqāma, a literary tale in rhymed prose that often features an itinerant trickster...Given their literary nature, these maqāmas should not be read as providing historical testimonies about the precise movement of the disease." Context is key.

Smithsonian Magazine reports that archaeologists excavating at the 17th-century Colony of Avalon in Newfoundland found seven wampum beads.

Hundreds of years ago, Indigenous inhabitants of North America created the small, cylindrical artifacts from mollusk shells...Indigenous groups of northeastern North America carved the beads from shells of quahog (clams) and whelk (sea snails). They incorporated the beads into belts and necklaces, which were sometimes used to mark important events. Later, they may have used the beads to trade with European settlers.

Allen Hazard of the Narragansett tribe makes wampum from quahogs and demonstrates the ancient craft in this video demonstration.

November is Native American Heritage Month. At the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), you can explore "800,000 objects and photographs and more than 500,000 digitized images, films, and other media documenting Native communities, events, and organizations. Find more information on the museum’s object collections and archival collections on this site." And from November 15, 2025–May 29, 2026, the "Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined in Glass" exhibition will run at the New York NMAI.

Glass artist Dan Friday is a Native of the Lummi Nation in the Pacific Northwest and explains his 25-year career working with glass.

Over at the New Books in Ancient History podcast, Raj Balkaran speaks to Karen Pechilis, Jarrod Whitaker, and Valerie Stoker about their new edited volume, A Cultural History of Hinduism, which goes from antiquity to the present and focuses on eight core themes—"Sources of Authority; Body and Mind; Social Organization; Identity and Difference; Politics and Power; Arts and Visual Culture; Lineages and Exemplars; and Global Contexts—allowing readers to compare developments across historical periods."

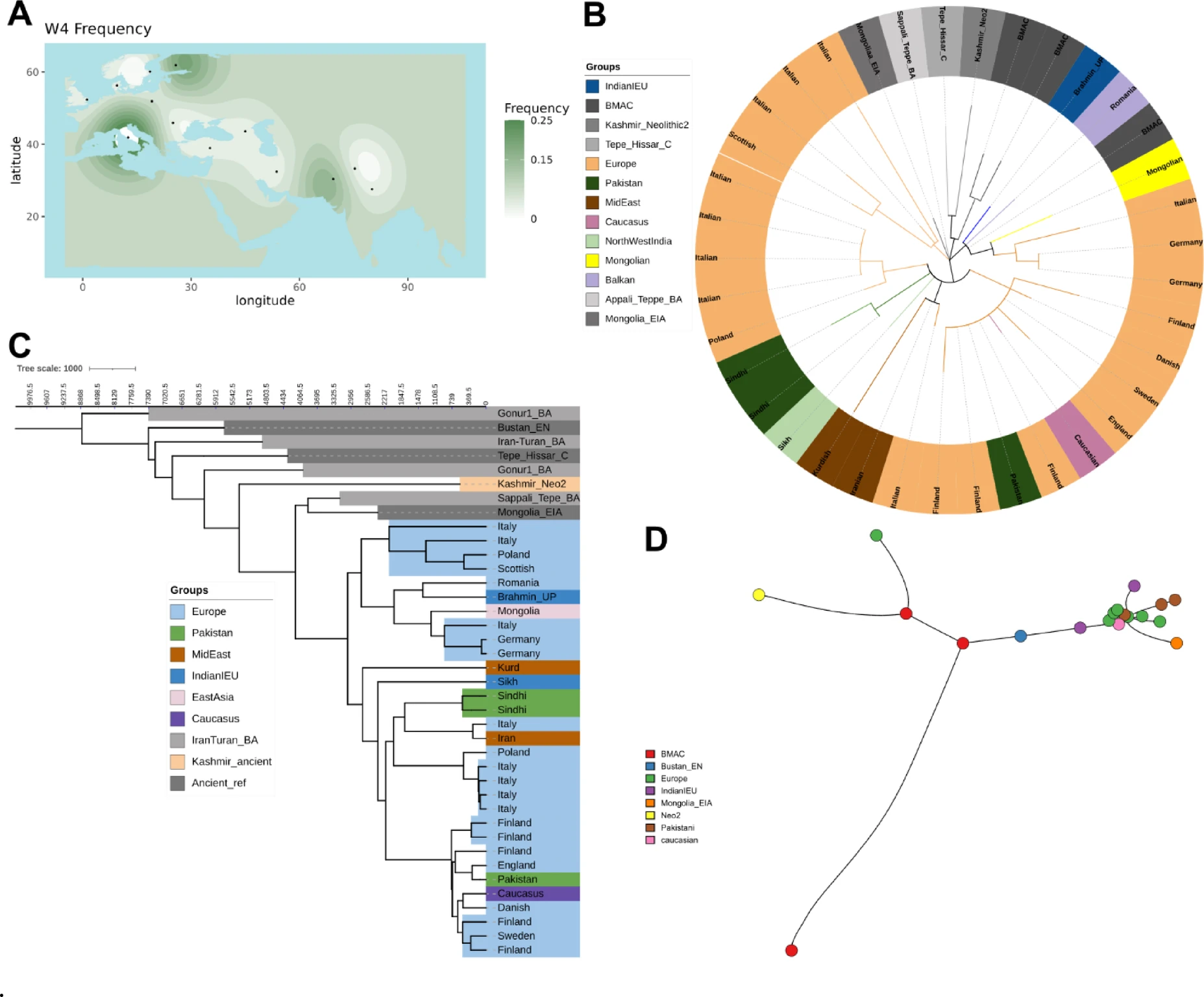

What can the archaeogenetics of Kashmir tell us about the cultural contacts in the area during the Middle Ages? Authors of a new, open access study in Scientific Reports reconstruct "for the first time the complete mitogenomes of Neolithic, megalithic and medieval individuals from the Burzahom archaeological site in Kashmir." The medieval population samples "showed clear signs of genetic contacts with Swat Valley historical and Central Asian Bronze age populations." We do love the potential for aDNA to elucidate cultural exchange.

Open access publications provide tools for engagement, research, and knowledge. They can also encourage cross-cultural comparison. Ancient philosophy expert Roopen Majithia compares Aristotle and the Gita in his book, The Highest Good in the Nicomachean Ethics and the Bhagavad Gita and in the new edited volume New Perspectives in Global Latin, the contributors look at "the role of the Latin language as cultural medium between West and East." I (Sarah here!) enjoyed Akihiko Watanabe's "Mercury and the Argonauts in Japan: Myths and Martyrs in Jesuit Neo-Latin."

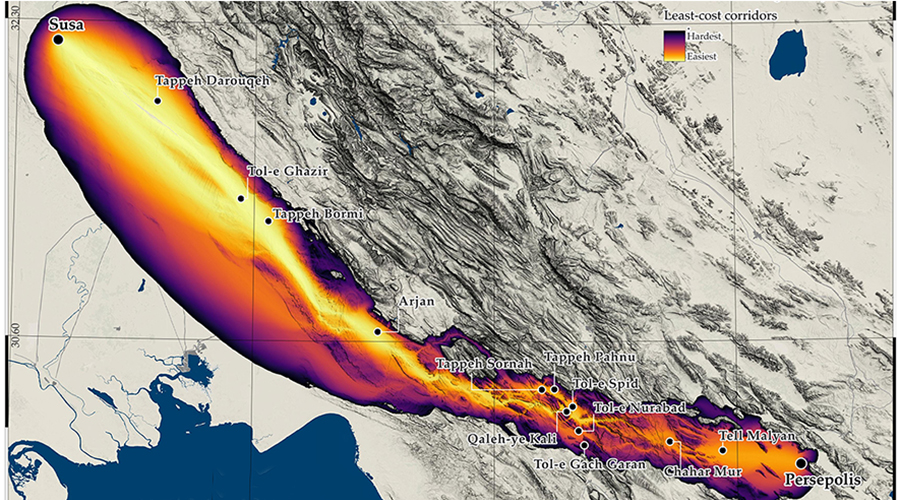

I am also a big fan of the new, open access study on "‘Royal’ road, ‘royal’ needs: a GIS-based approach to Achaemenid court logistics between royal capitals of Susa and Persepolis." It proposes a redefinition of the concept of the Achaemenid ‘Royal’ Road (550-330 BCE) by applying GIS methodologies and least-cost corridor (LCC) modelling "to identify broader areas that better reflect the variability of ancient travel."

Good news: The wall paintings of the Dura-Europos Synagogue, installed at the Syrian National Museum in Damascus, have emerged intact from over a decade of Civil War. A delegation of rabbis and scholars were able to visit the installation last month. Meanwhile the proceedings of the 2022 conference Dura-Europos: Past, Present, Future , edited by Lisa Brody and Anne Hunnell Chen have now been published in open access.

Karen Stern speaks on "Inscription, Touch and Worship in the Synagogue of Dura Europos"

The Classical Association of the Middle West and South (CAMWS) has announced the Anthony Fauci Award in STEM and Classics. The $500 annual award "recognizes an undergraduate student who demonstrates outstanding work in both Classics and a STEM discipline (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics)." Apply by January 30, 2026. Also? At the University of Notre Dame they have a great essay: "A Classicist in the Lab: How Studying the Humanities Helps Me Succeed as a Biology PhD Student" by biologist Stephanie Morgan.

I have increasingly found that my continued engagement with classical studies as an academic discipline has imbued me with many of the basic skills I use as a scientist. So, here are the skills I learned as a classicist that I now use as I build my scientific career

What is the smell of history and is it nasty? Over at the Scientific American, Gayoung Lee interviews Barbara Huber, an archaeochemist at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany.

This way of perception is kind of “participating” in the past. If you enter a room and you can actually smell how it must have smelled in an ancient mummification room in ancient Egypt—and you see all the raw materials and everything—then you’re in a different way being immersed in history and in learning.

In book review news, in the London Review of Books, there is a review of Euphrosyne Doxiadis' The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt and a great review of Shane Bobrycki's The Crowd in the Early Middle Ages. Then, in the Times Literary Supplement, Johanna Hanink reviews Hal Drake's The Wisdom of the Ancients: Four ideas that changed the world and Josephine Quinn examines Augustine the African by Catherine Conybeare for the New York Review of Books.

If you want to know what we are reading this week? Kim Bowes' Surviving Rome: The Economic Lives of the Ninety Percent came out on Tuesday alongside Shaily Patel's new Smoke & Mirrors: Discourses of Magic in Early Petrine Traditions. So many books to read over the winter break!

And, finally, a fecal fable ... a sh*t story: "Ancient poop from Mexico’s ‘Cave of the Dead Children’ teems with parasites." Turns out that 1) pinworms were lethal back in the day and 2) the dry heat of the state of Durango is really good at preserving poop for one-and-a-half millennia. Yes, there are pictures. Proceed with caution. Just trying to keep things coprolite and airy! 🪱

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Vol. 68, No. 1 (2025) Orosius through the Ages

Cahiers du Centre d’Études Chypriotes Vol. 55 (2025) #openaccess Chypre, de l’Antiquité tardive à la fin de l’époque médiévale (LA3M, Aix-en-Provence)

Classica Cracoviensia Vol. 28 (2025) #openaccess

Classical Receptions Journal Vol. 17, No. 4 (2025) NB Maoz Kahana "The return of the gods: Greco-Roman mythology in eighteenth-century rabbinic lore"

The Classical Review Vol. 75 , No. 2 (2025)

Collectanea Philologica Vol. 28 (2025) #openaccess Chrestomatia antyczna. In memoriam Joannae Rybowska

Latomus Vol. 84, No. 2 (2025)

Mnemosyne Vol. 78, No. 6 (2025) NB Matthew Chaldekas "The First Female Philosophers in Ptolemaic Alexandria: Prosopographical Perspectives"

Religion in the Roman Empire Vol. 11, No.2 (2025) The Epigraphy of Roman Religion: Problems and Solutions

Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica Vol. 31 (2025) #openaccess

Aestimatio: Sources and Studies in the History of Science Vol. 5 (2024) #openaccess

Journal for the History of Astronomy Vol. 56, No. 4 (2025) NB D. Graham J. Shipley, "Ancient Greek observations of T Coronae Borealis? Data and methodologies"

Journal of Ancient Philosophy Vol. 19 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess NB Christen Zimecki, "Plato’s Conception of Pleonexia as Structural Excess"

Journal of Indian Philosophy Vol. 53, No. 5 (2025)

Philosophy East and West Vol. 75, No. 4 (2025) Pragati Sahni "In Search of an Ethics for Plants: A Brief Exploration of the Early Writings of Jainism and Buddhism"

Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy Vol. 36, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde Vol. 152, No. 2 (2025)

Frankokratia Vol. 6, No. 2 (2025) The Friary of St Francis in Venetian Candia: Art, Learning, and Sources

Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 59 (2025) #openaccess

Studia Historica. Historia Medieval Vol. 43 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess The Peasant Mode of Production in the Early Middle Ages

Archaeological Dialogues Vol. 31, No. 1 (2025)

Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt Vol. 54 No. 4 (2024) #openaccess

Journal of Urban Archaeology Vol. 12 (2025) 'Lost Cities and Legacy Data’

Workshops, Lectures, and Exhibitions.

At 5pm EST today (Thursday, November 6th), the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard will host a discussion of "African connections with Anglo-Saxon England? New insights from ancient DNA" featuring Joscha Gretzinger with comments by Emmanuel K. Akyeampong and John Hines. On Tuesday, November 11, at 5pm Dr. Gretzinger will also present, together with Zuzana Hofmanová on "The Origins and Early Migrations of the Slavs" Online attendance is welcome for both talks.

At the Getty Villa, a free in person and online lecture from archaeologist Camille Reiko Acosta will discuss "Merchants and Mercenaries: The Archaeology of Greeks in Egypt." It will occur on Sunday, November 9 at 2 pm PT. You are free to attend in person (register here) or to watch online via Zoom (register here). This program complements the exhibition Sculpted Portraits from Ancient Egypt on view at the Getty Villa through January 25, 2027.

On December 5, 2025 at 1:30 PT, ancient medicine specialist Colin Webster will present “Greco-Indian Medical Interactions” for the Huntington Library & Southern California Society for the History of Medicine. To register for the online talk, contact Gideon Manning (gideonmanning@socalhistmed.org).