Pasts Imperfect (11.20.25)

This week, media psychology and classical reception specialist Kristen Leer discusses Ancient Egypt in horror movies and the problems surrounding "Egyptomania." Then, mapping the thousands of miles of Roman roads, protests hold up the opening of the MOWAA, tarot cards and Platonic philosophy, opium in Ancient Egypt, stone tools excavated in Kenya's Turkana Basin, a new book on the chorus in Greek tragedy, remembering the Council of Nicaea on its 1700th anniversary, Arum Park discusses a recent conference on Classics and Asia, new ancient world journals, and much more.

Egypto-Horrormania: How Horror Films Construct Their Fascination With the Ancient Egyptian World by Kristen Leer

Cinematic ventures into the ancient world are often adventurous, exciting, and climactic, but frequently inaccurate. Still, our emotional fascination with the ancient world underscores a deeper desire to understand cultural practices surrounding mythology, art, and death. Horror films have fostered this cinematic, fantastical, and oft-orientalized representation of the ancient Near East, particularly of Egypt. This is partially a result of Egyptomania, particularly prevalent in 1822 after the decipherment of hieroglyphs that first shaped the imagination and fascination of Egyptian culture.

“Egyptomania” refers to a period of renewed interest in ancient Egypt. It is not just a modern phenomenon. Romans had a deep fascination and colonial obsession with Egypt that particularly took hold in the late Republic into the period of the early Roman Empire, following Egypt’s annexation as a province in 30 BCE. The 19th-century version was sparked by Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign in 1798, where scientists and scholars undertook one of the largest documentations of Egyptian culture. This included them taking ancient Egyptian artifacts without consent, which is still a point of great tension to this day with the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum. At the time, forms of media that captured their expeditions or discoveries were maps and drawings that were published to the public, influencing a specific type of engagement with Egypt primarily through these documentations of its literature, art, and architecture. In doing so, these early records created and shaped specific representations of Egyptian culture that continue to be evident in modern portrayals.

From Egyptian imagery being used in decorative arts and architecture to engaging with thematic components of their mythology, various elements of ancient Egyptian culture captured the attention of many Europeans, but no more than mummification. The second wave of Egyptomania occurs in the the earlier part of the 20th century with the discovery of Tutankhamun in 1922 (see Riggs 2022). Nevertheless, until the second wave, the interest in ancient Egypt and the mummy was sustained through evolving artistic mediums. It isn’t just the preservation imagery or the tomb’s iconography of the mummy, but what it represents – our unavoidable venture into dying and the afterlife, and how the Egyptians have created unique relationships and traditions with the afterlife.

Mummies were a key element of the obsession with ancient Egypt that inspired artistic and literary creativity–the renowned Gothic writer Edgar Allen Poe wrote a short story, “Some Words With a Mummy” (1850), capturing the reflection of scientific progress and popular interest in mummies. Additionally, Egypt still remained a source of focus as film became a growing medium with The Mummy (1911). But this focus on the mummy underscores a morbid relationship with people who, in ways, objectified ancient Egypt’s relics by having “mummy unwrapping parties.” It is no wonder that horror films toe the line of reinforcing genuine interest in the ancient world and culture, but also reflect objectification, exaggeration, and exotification of specific elements such as the mummy.

The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 continued the growth of Egyptomania, particularly through film. A decade later, the ancient Egyptian world came forth onto the screen, becoming an industrial and cultural success. The 1932 film The Mummy, part of the Universal Monsters franchise, focuses on Imhotep, an ancient Egyptian mummy who was killed for attempting to resurrect his dead love, princess Anck-es-en-Amon. After being discovered and resurrected by archaeologists, unleashing his curse, he assimilates into modern society and begins his attempt to resurrect Anck-es-en-Amon. He finds her tomb and attempts to make Helen Grosvenor, who resembles the princess, her reincarnation. But Imhotep’s plans are foiled. The film constructs a clear illusion of Egyptian culture being assimilated and reinvented in the modern Western world, with Imhotep’s resurrection serving as a metaphor for cultural integration. This underscores the evolving issues of appropriation of non-European culture and the imposition of Western ideals through artistic mediums.

The Mummy relies on an exaggerated exoticization of the dangers associated with assimilation, echoing common tropes in Universal monster films where the monster threatens men (e.g., masculinity, cultural authority), women (e.g., desirability), and society as a whole (e.g., destabilizing Western ideals). To emphasize this representation, films go so far as to put their spin on Egyptian mummification, such as the reanimation of them. There is no evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians believed in reanimated mummies. Rather, Egyptian sources such as the Book of the Dead talked about life in terms more of the process of assisting the soul through the afterlife. Nevertheless, the westernized mummy in horror films wouldn’t exist without this key characteristic of being able to reanimate and, in turn, represent the dangers of non-European Western cultures.

Tropes have power, particularly in visual media. The sensational elements established in the 1932 Mummy film were replicated in multiple adaptations throughout the 1940s, including a comedy horror crossover in Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955), and continued to shape portrayals of Egypt in the later decades. It was not until The Mummy (1999) that we see a postmodern remake of the classic horror narrative. In this version, Imhotep and Anck-su-namun return, not only amplified in their destructive power and framed within a more adventurous storyline, but also carry forward the original thematic threats. The western anxieties embodied by the mummy in the 1930s are sustained and reimagined for a 21st-century audience.

These anxieties have never stopped creators or audiences from returning to ancient Egypt as a source of horror through the lens of an otherized culture. The 21st century continues to revisit and reinvent the mummy narrative: from expanding The Mummy (1999) franchise into The Scorpion King (2002) as more action-adventure, to fusing Egypt with other supernatural beings, such as the ancient vampire queen Akasha in The Queen of the Damned (2002). Found-footage horror explores Egyptian archaeology in The Pyramid (2014). One of the most exaggerated and spectacular transformations of the trope is in The Mummy (2017), starring Tom Cruise. Video game creators have also taken an interest in ancient Egypt, embedding it within acclaimed franchises such as Assassin’s Creed and a standalone first-person horror game, Amenti (2025).

The use of ancient Egypt and mummies in films, and now in other forms of media and digital technologies, demonstrates the persistent fascination with ancient Egypt, while simultaneously revealing how horror’s own Egyptomania often walks a fine line between cultural curiosity, sensationalism, and exoticism. Such representations lead viewers to think about the deeper historical and cultural tensions behind how depictions of ancient Egypt are curated, especially for a Western audience. This is particularly relevant as not only Universal monsters (e.g., Frankenstein’s monster) and other monstrous creatures (e.g., the Werewolf) are being revised and reinterpreted in our contemporary cinema, in addition to talk of reviving the 1999 Mummy series. Recasting of these figures in the modern day prompt reconsideration of how the ancient world is being depicted and the thematic aspects they attempt to underscore in their work.

Kristen Leer is a PhD candidate in Communication and Media at the University of Michigan. She received her B.A. in Psychology, Classic Civilization, and Religious Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

Where were the roads of Rome? Popular Mechanics reports on the digital humanities project known as Itiner-e, a mapping project paved with Pleiades geodata to help thousands of miles of Roman roads come back to life. Their new study is now published open access in the journal Scientific Data. There were likely 62,000 additional miles of roads not previously known to modern researchers, "nearly doubling the length of the Roman road network" we know of.

In Archaeology News, they report on the collaborative archaeological work between the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), the British Museum, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) and several other research teams within Benin City, Nigeria. The excavation uncovered archaeological layers that predate the founding of the kingdom of Benin, "suggesting early settlement in the area during the first millennium AD. Other deposits correspond to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—the height of Benin’s power." Although the new museum was supposed to open early this month, protests and conflict over the name and mission of the museum have delayed the opening.

Over at the University of Michigan, classicist and ancient philosophy expert Sara Ahbel-Rappe talks Tarot and Platonic philosophy in a series of videos. In her class “Tarot and Western Spirituality,” students learn about the ancient world’s cryptic histories alongside its philosophical and cultural transformations and even create their own Tarot decks.

This week, Hetan Shah, Chief Executive of the British Academy and Chair of Our World in Data, wrote about the problems at the British Library in an article called "The British library is in crisis: why does nobody care?"

Few people are aware that the Library has not yet recovered from the cyberattack and the impact this has had on the research community. The archives and manuscripts online catalogue is still not available, as well as various other catalogues such as those for photographically illustrated books. This has been disastrous for university teaching, research and publication in many humanities disciplines. Students who began their doctorates in September 2023 have now entered their final year of funding without access to British Library digitisations and, for long periods, without access to British Library manuscripts.

As Shah remarks: "We ignore research infrastructures at our peril." ἀμήν.

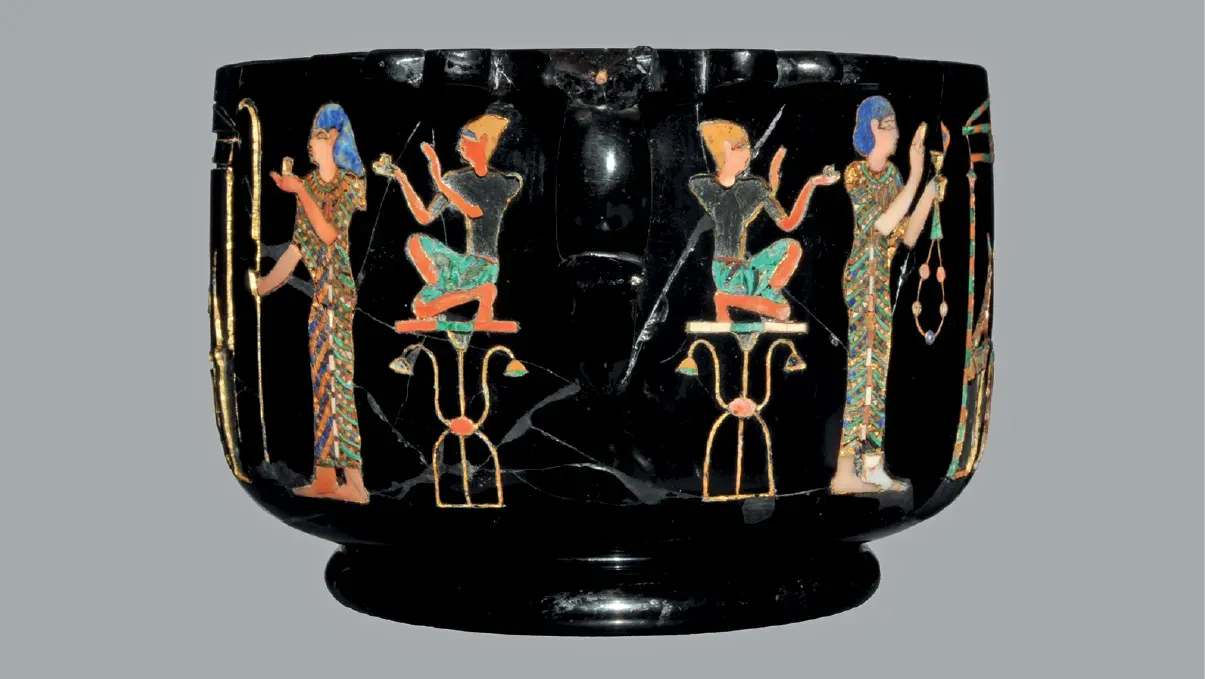

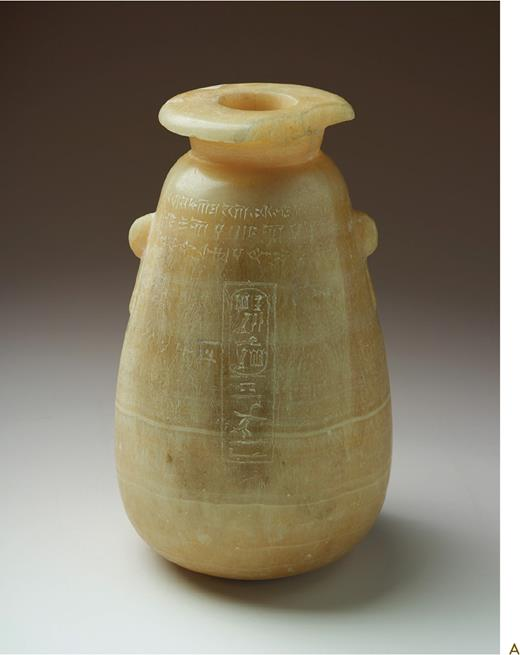

And at Yale, the Yale Ancient Pharmacology Program (YAPP) has discovered traces of opium in ancient Egyptian society. Researchers are now investigating alabaster vessels that traveled across ancient empires. Read more about the new research in the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies.

The provenances of the intact vessels are generally unknown, the researchers said, but they at least span the reigns of Achaemenid emperors Darius, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes, a period covering 550 to 425 BCE.

Stone tools excavated in Kenya's Turkana Basin show that early humans adapted to a fast-changing environment. The international team at the archaeological site of Namorotukunan continues to analyze the cutting-edge (pun absolutely intended) technology created and further developed by generations of people.

In new book news, Rosa Andújar has a new book out with Cambridge Press, Playing the Chorus in Greek Tragedy. Huiyi Wu and Mackenzie Cooley also have a new open access volume on Knowing an Empire: Early Modern Chinese and Spanish Worlds in Dialogue and compares the two empires "[t]hrough a new methodology of “juxtapositional comparison" that parallels difangzhi 地方志 (local gazetteers) of China and the relaciones geográficas of the Spanish world. Read it for free here. And finally, Maja Gori and Martina Revello Lami have a new, open access edited volume on Learning, Teaching, Changing African Archaeology out in the Ex Novo: Journal of Archaeology.

Around 4,200 years ago, the residents of the ancient city of Caral in Peru had to evacuate due to a climate crisis. Archaeologist Ruth Shady and her team are analyzing temple pyramid art which depicts the consequences of a mega-drought, and the subsequent moving and evolution of an ancient people.

Over at The Conversation, Victoria Gibbon, Jessica C. Thompson, and Sianne Alves ask a constantly-evolving question: who speaks for the dead? As students of the ancient world, we must consider the ethics of ancient DNA.

Consent is not yet universally mandated nor typically obtained in aDNA research, despite growing awareness of its importance over the past two decades. What is more, the concept of “informed consent” as developed in the clinical medical world is deeply rooted in a western idea of individual autonomy. It assumes that most medical decision-making occurs by individuals, rather than communities. And there are challenges applying it to people who are no longer alive.

In a blog post, Peter Adamson reflects on, and defends, the use of the term "philosophy" to describe intellectual tradition outside of the "European Tradition." This approach is reflected in the latest installment of his History of Philosophy (without Any Gaps) book series, co-authored with Chike Jeffers, Africana Philosophy from Ancient Egypt to the Nineteenth Century. Jeffers recently discussed ancient Egyptian philosophy on the Examined Life Podcast.

Finally, it is the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea. And historian of late antiquity Young Kim curated a forum with ten other historians of Christianity. Read their contributions here: "Reflections on Nicaea at 1700: A Forum on the Legacy of the Council and the Creed" for free in Church History. And big congrats to the one and only Brett Whalen for taking over the journal as Editor-in-Chief.

Classics and Asia by Arum Park

This month, the University of Arizona hosted a Symposium titled “Exploring the Intersection of Classics and Asia.” Drs. Ellen Bauerle (University of Michigan Press), Katherine Lu Hsu (College of the Holy Cross), Young Richard Kim (University of Illinois-Chicago), Tori Lee (Davidson College), Dominic Machado (College of the Holy Cross), Kelly Nguyen (UCLA), and Chris Waldo (University of Washington) joined symposium organizer and Associate Professor of Classics Arum Park (University of Arizona) to think and talk about how Classics and Asia could be studied together and to what end. Featuring presentations by Drs. Nguyen, Machado, and Waldo, as well as a classroom visit and public roundtable discussion by all symposium guests, the two-day event covered a wide range of topics: the deployment of Greco-Roman antiquity for both oppressive and liberatory purposes in Vietnam; the utility of comparative approaches for understanding the literature of civil war in Rome and Sri Lanka; the centrality of classics in Asian American performance art; integrating scholarly and community work; and models of intellectual collaboration and support, just to name a few.

As wide-ranging as it was, the symposium cohered around a central purpose: to build and expand mutually supportive communities of knowledge that would push against disciplinary constraints. In varying but complementary ways, each of the presentations and discussions was driven by the twin hopes of expanding knowledge through human connection and forging human connection through the expansion of knowledge. The symposium intentionally challenged the culture of isolated, competitive, and even combative knowledge production that can be pervasive in academia. Participants and attendees alike remarked on the transformative experience of being in an academic space that was equal parts provocative, rigorous, collegial, and welcoming. “Exploring the Intersection of Classics and Asia” reflected the work of the new book series co-edited by Arum Park and Young Kim, “Classics and Asia at the Intersections,” which itself was born of the advocative and intellectual mission of the Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus. All of these efforts represent and participate in the current, ongoing, and growing movement towards greater equity and inclusion in Classics. But the symposium was also a celebration, of a home built for the study of Classics and Asia and those who embark on it. And like all the best new homes, it was built with the expectation of renovation and expansion, to accommodate present and future residents alike.

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Classical Antiquity Vol. 44, No. 2 (2025) NB Jessica L. Lamont "Time, Festivals, and the Ἐννεατηρίς in Archaic and Classical Greece"

Classical Journal Vol. 121, No. 1 (2025)

Circe de clásicos y modernos Vol. 29 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Frankfurter elektronische Rundschau zur Altertumskunde No. 56 (2025)

Gephyra Vol. 30 (2025) #openaccess

Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies Vol. 65 No. 4 (2025) #openaccess

Historikà Vol. 14 (2024) #openaccess

International Journal of the Classical Tradition Vol. 32, No. 4 (2025) NB Giulio Leghissa, "The Influence of Classical Texts in Western Descriptions of Egypt Between the Sixteenth and the Twentieth Centuries"

Journal of Greek Linguistics Vol.25, No. 2 (2025)

Lingue antiche e moderne Vol. 14 (2025) #openaccess

Opuscula Vol. 18 (2025) #openaccess

Studies in Late Antiquity Vol. 9, No. 4 (2025) Paleoscience and the Study of Late Antiquity

Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie Vol. 107, No. 4 (2025)

History of Philosophy Quarterly Vol. 43, No. 3 (2025) NB Osman Nemli "Class is the Measure: Georg Lukács and A Materialist Reading of the Presocratics"

The International Journal of the Platonic Tradition Vol. 19, No. 2 (2025) Dedicated to Suzanne Stern-Gillet

Augustinianum Vol. 65, No. 1 (2025)

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 87, No. 4 (2025)

Dead Sea Discoveries Vol. 32, No. 3 (2025)

Journal for the Study of Judaism Vol. 56, Nos. 4-5 (2025)

Journal of Ancient Judaism Vol. 16, No. 3 (2025)

Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 144, No. 3 (2025)

Patristica Nordica Annuaria Vol. 39 (2024) #openaccess NB Alexandra Lembke-Ross "Maternity and Mortality: A Matricentric Reading of the Prison Diary of Perpetua"

Revue d'Etudes Augustiniennes et Patristiques Vol. 71, No. 1 (2025)

Revue de l'histoire des religions Vol. 242, No. 4 (2025) Entre le dire et le faire : pour un lexique du religieux romain

Revue de Qumran Vol. 37, No. 1 (2025)

Vigiliae Christianae Vol. 79, No. 5 (2025)

AlʿUsur al-Wusta Vol. 33 (2025) #openaccess

Indo-Iranian Journal Vol. 68, No. 3 (2025)

Journal des Médecines Cunéiformes No. 42 (2023) #openaccess

Maarav Vol. 29, Nos. 1-2 (2025)

Manuscript Studies Vol. 10, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Mediaevalia Vol. 46 (2025)

The Medieval History Journal Vol. 28, No. 2 (2025)

Acta Archaeologica Vol. 95, No. 1 (2024) GIS and Roads Innovative Digital Frameworks for Route Analysis in Antiquity

Archäologischer Anzeiger No. 1 (2025)

Cambridge Archaeological Journal Vol. 35, No. 4 (2025)

Isis Vol. 116, No. 4 (2025) Focus: Is Deep History White?

Digital Scholarship in the Humanities Vol. 40, No. 4 (2025)

Lectures, Workshops, and Exhibitions

On December 3, 2025, Isabel Grossman-Sartain will run an ISAW-NYU "Expanding the Ancient World Workshop" focused on "State Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean and Mesopotamia: Egypt, the Neo-Assyrians, and Rome." Registration is at this link.

The 2026 AAH Annual Meeting will take place in person at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, IA from April 16-18, 2026. We invite abstracts for papers of 15-20 minutes in length. Please submit anonymous abstracts for one of the panels of no more than 500 words to the AAH 2026 Form by December 1, 2025.