Pasts Imperfect (10.9.25)

![Unknown Artisan, " [Obverse of a] Token with an Egyptian Obelisk [from Nikopolis, Egypt] and a Temple," 1-50 CE, tessera, cattle bone, Roman with Greek inscription on reverse](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/10/9010.jpg.webp)

This week, art historian and AAR Classical Summer School attendee Lachelle Oglesby discusses obelisks, Roman colonialism, and lived experiences in ancient Rome. Then, a new video game allows you to "reloot" African cultural heritage from museums, bronze mirror-making in the Western Han dynasty, the Nubian ivory trade within the Levant, a new book on ancient Egyptian art at the Art Institute, understanding the selfish satraps in the Persian Empire, new podcasts on the history of Classics and Hawaiian archaeology, indigenous readings of the Bible, new ancient world journals, and much more.

Restoring the Egyptian History of the First Neferibre Obelisk

This summer, I attended the American Academy in Rome’s Classical Summer School, where each participant produced a site report. I chose Bernini's Palazzo Montecitorio and introduced my group — largely philologists and educators — to art historical research methods. I framed the report as an object biography, an approach that treats objects as having lives, experiences, and even relationships with other objects.

The 22-meter obelisk standing in front of the Palazzo was once known as the Solare. Here, I refer to it as the First Neferibre Obelisk, in honor of its Egyptian origins. Most scholarship on the Neferibre Obelisks begins with Augustus, who brought them to Rome in 10 BCE. In a posthumous symbolic victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII, Augustus broke the obelisks for sea transport and installed it as the gnomon of his Solarium Augusti. Gnomons are the pointers on sundials, and tell time by the shadows they cast when the sun shines on them. Pliny writes that the sundial stopped functioning shortly after an earthquake, yet it remained active in the imperial imagination, appearing in a second-century CE personification of the Campus Martius on a base dedicated to Antoninus Pius and Faustina.

The First Neferibre obelisk still stood in the early ninth century CE, noted in a Christian pilgrimage itinerary discovered in sixteenth-century Switzerland. It was likely toppled sometime after, perhaps by the powerful earthquake of May 849, and later rediscovered in 1512 by a barber digging a latrine—though Pope Julius II declined to have it properly excavated. Rediscovered again in 1748, the obelisk was re-erected by Pope Pius VI, who filled missing sections with brick faced in rose granite from the Column of Antoninus Pius and topped it with a bronze globe. It has stood there since 1792.

This account skips over more than five centuries of the obelisk’s earlier life. I want to do my best to fill in those gaps, starting with what an obelisk is. Obelisks symbolized the sun god Ra. Egyptians saw them as petrified sunbeams and erected them in pairs outside of his temples. They were quarried and carved lying flat, transported horizontally, and raised upright once they reached their destination. The tapered shaft and pyramidion were usually inscribed with dedicatory hieroglyphs. Obelisks were religious and political symbols, but they were also wayfinding tools, memory anchors, and markers of identity for ancient Egyptians.

In the 8th century BCE, invading Nubian kings tried unsuccessfully to use obelisks to legitimize their rule. They were later overthrown by Psamtik I, a native Egyptian who reunified Upper and Lower Egypt and founded the 26th Dynasty. His grandson, Psamtik II (r. 595–589 BCE), took the royal name Neferibre, meaning “Perfect Heart of Ra.” In 592 BCE, Neferibre led a decisive campaign against Kush to prevent their return to power. Soon after, obelisks bearing his name were quarried in Aswan and erected at Heliopolis, before the temple of Ra. I speculate that they marked a renewed native sovereignty, celebrating a dynasty that expelled foreign rulers and extended its reach.

According to Strabo, the obelisks were toppled during the Persian king Cambyses’ invasion in 525 BCE. No record survives of what happened to them when Alexander the Great defeated the Persians and took Egypt in 332 BCE. They may have been restored to their former glory — possibly with the support of the early Ptolemies, which would have aligned with other Ptolemaic legitimization strategies. Early on, the Ptolemies allowed native Egyptians to maintain control of political and religious offices, and were soon actively participating in local religion, commissioning pharaonic-style busts, and presiding over a hybridizing society. The idea that the Ptolemies may have supported — or even initiated — the restoration of a monument so deeply tied to local identity risks romanticizing Greek colonization, which was met with much resistance.

Aside from Neferibre himself, Cleopatra is probably the most important figure in the biography of the Neferibre Obelisks. She was the daughter of Ptolemy XII; her mother’s identity is uncertain. Plutarch notes she was the only Ptolemaic ruler to speak Egyptian — a gesture that, political or not, could have resonated deeply with native Egyptians after three centuries of Greek rule.

If the First Neferibre Obelisk held memory, Cleopatra’s death may have registered as a cataclysm, especially if it still embodied its original purpose: celebrating Neferibre, a king who briefly ensured native sovereignty. Cleopatra’s death extinguished any hope of native rule. The obelisk was then broken, separated from its twin, and violently removed from its home to begin a new life as a Roman trophy.

The inscriptions resonate strongly in this context. Neferibre dedicated the obelisk to Ra; Augustus later re-dedicated it to the sun, nominally preserving its purpose even as Rome strips away Egypt’s sovereignty. Pliny inadvertently links Egypt’s monumental past to Rome’s mythic prehistory by mentioning Troy alongside Ramses the Great. He later claims that Cambyses spared the Neferibre Obelisk while burning the city, implying reverence for the monument. Strabo, however, notes that many obelisks were damaged during Cambyses’ conquest, including those Augustus later looted. Centuries later, Marcellinus claims Augustus refrained from taking one out of “reverence” for Ra. In reality, Augustus likely seized every obelisk he could.

What did it feel like to be a Roman citizen, walking through a city where the emperor had subdued such an ancient land? A small red granite souvenir of the obelisk’s base, inscribed with the Augustan text, prompts questions about how the plundering of Egyptian sacred spaces was represented, circulated, and received across different audiences. But how much did the Romans know about the obelisk’s pre-Augustan life? Were these histories being told? And what did it feel like to be a native Egyptian — enslaved, traveling, or living in Rome — encountering this monument marking the passage of time in another empire?

Lachelle Oglesby is a graduate student in Art History at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

A Note from Evan Jewell (2023 Fellow), Director of the AAR Classical Summer School: Directing the Classical Summer School has been a real joy over the past two years—not least because of participants like Lachelle, who have made the most of the program and its opportunities to develop their ideas—such as her work on obelisks and imperialism—and their knowledge base of the physical city of Rome and surroundings, from visiting archaeological sites, many digs (last summer we visited no fewer than six!), museums and hands-on workshops focused on pottery to epigraphy. The CSS also becomes a unique learning community, not least because students and teachers of all levels and backgrounds have to engage with each other, not just on matters of content, but also pedagogy. Seeing seasoned Latin school teachers share their pedagogy with new graduate students and witnessing the revelations that emerge in those conversations has been one of the best things about the school and how I hope it furthers the study of the ancient world beyond academia and in our schools and museum education departments. So, please consider applying for 2026!

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

At CNN, they discuss a new video game called Relooted, which allows gamers to repatriate African cultural heritage from museums—including the Benin bronzes. "Created by South African game developer Nyamakop, the game, to be released on PC and Xbox, is set in a futuristic Johannesburg, South Africa. The crew is composed of scientists, computer programmers and MMA fighters — rather than seasoned criminals — and guided by the fictitious Professor Grace, a retired South African art historian frustrated by the glacial rate of restitutions."

In Archaeology Magazine, Dario Radley reports that researchers at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)'s archaeo-metallurgy lab "have tracked the evolution of bronze mirror-making back to a time of economic recovery and state-backed reform during the reigns of Emperors Wen (180–157 BCE) and Jing (157–141 BCE) of the Western Han dynasty." The Journal of Archaeological Science published the new study and the whole issue is kind of a banger. Their article on "A thousand years of Nubian supply of sub-Saharan ivory to the Southern Levant, ca. 1600–600 BCE" is a fascinating look at African elephant ivory trade networks stretching from Nubia to the Levant.

The Art Institute of Chicago has published its new book on the Egyptian antiquities at the museum online (and open access). Ancient Egyptian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago is a great teaching resource with contributions from Egyptologists like Fatma Ismail and from curator Ashley F. Arico, among many others. If you are at the AI, stop by and see “Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies.” It is a splendid exhibition on now until January 4, 2026. Catlett was an incredible artist and sculptor who was also the recipient of the first master's of fine arts degree in sculpture granted by the University of Iowa.

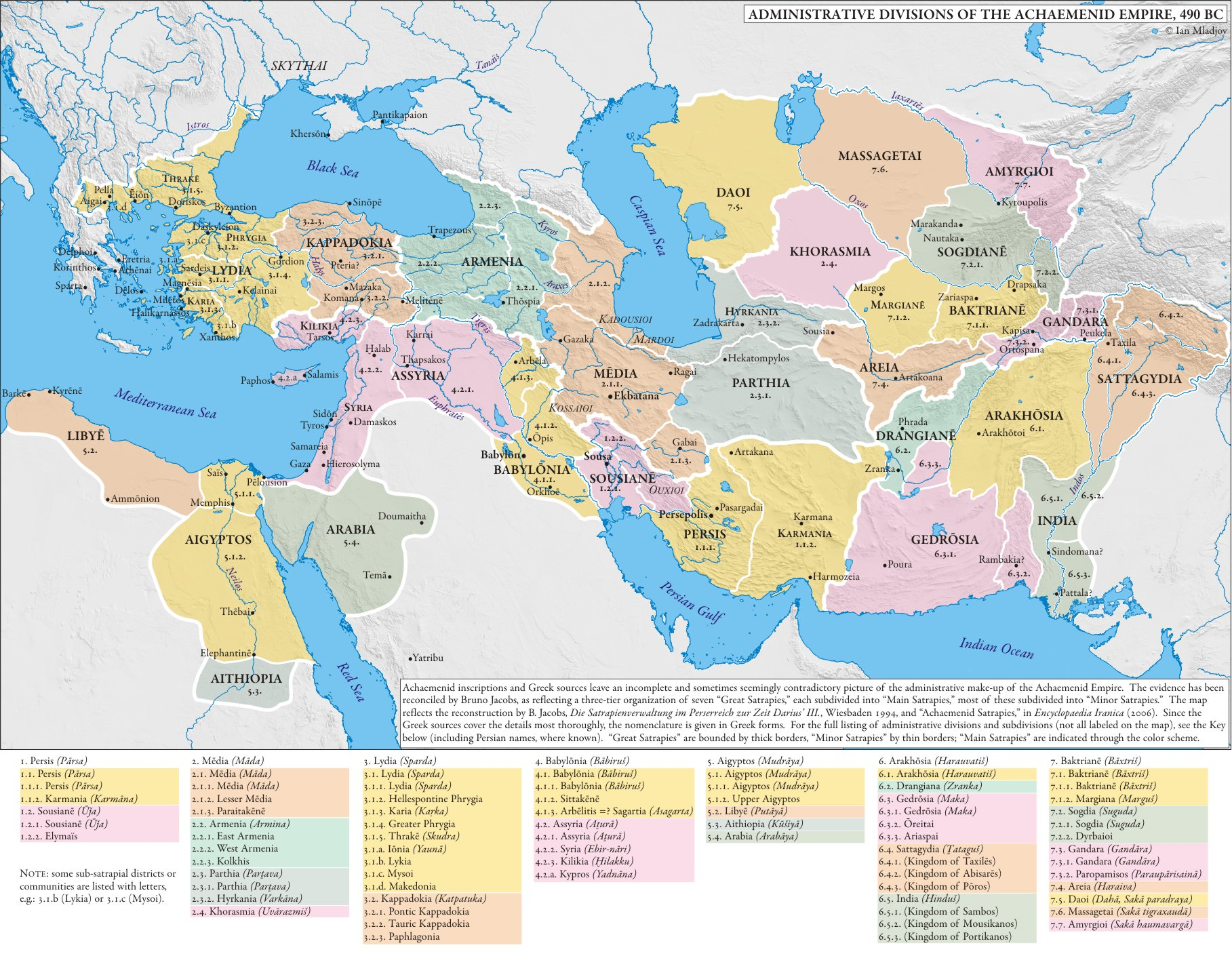

Over at the UC Press Blog, Rhyne King, author of the new The House of the Satrap: The Making of the Ancient Persian Empire, doesn't ask why the Persian Empire fell, but rather "how did the Persian Empire endure at its continental scale for over two centuries?" King looks at "how the satrapal houses worked as a unified imperial system[, taking] readers on a tour across the empire: Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan." What he found in common? Selfishness.

They found a Roman wood workshop in Gaul! And lots of writing tablets along with children's size wooden shoes. "Subsequent investigations [to the 2020 excavation], focused on material recovered from four wells, have provided an exceptional collection of organic remains—wood, seeds, pollen—whose preservation, after centuries submerged in a waterlogged, light- and oxygen-deprived environment, sheds new light on manufacturing and daily life in Roman Gaul." Now, just remember to wear these sandals with Roman socks.

In November, PI contributor and scholar of early Christianity Christopher Hoklotubbe has a new co-authored book coming out, Reading the Bible on Turtle Island: An Invitation to North American Indigenous Interpretation. And over at the Lesche podcast, Dan-el Padilla Peralta discusses his new book, Classicism and Other Phobias (Princeton UP 2025). At The Ancients podcast, they speak to Hawaiian archaeologist Patrick Kirch, to "delve into the impact of Polynesian settlers on Hawaii's pristine ecosystem, the use of petroglyphs, and the development of highly stratified societal structures shedding light on Hawaii's ancient past."

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Aitia Vol. 14 (2024) #openaccess Mythe et pensée dans la poésie hellénistique et dans la littérature grecque impériale

Classical Philology Vol. 120, No. 4 (2025)

Dialogues d'histoire ancienne Vol. 51, No.1 (2025)

Dialogues d'histoire ancienne Suppl. 30 (2025) Collections et archives : quelles enquêtes pour l’historien de l’Antiquité ?

Greek and Roman Musical Studies Vol. 13, No. 2 (2025)

Hesperia Vol. 94, No. 3 (2025)

Historia Vol. 74, No. 4 (2025)

Illinois Classical Studies Vol. 50, No. 1 (2025) Fake News is or as Invective in Ancient Texts

Mélanges de l'École française de Rome - Antiquité, Vol. 137, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess La pratique de l’écrit dans les lieux de culte en Italie, Hispanie et Gaule (IVe s. av. n. è-IIIe s. de n. è)

Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 86, No. 4 (2025)

Méthexis Vol. 37, No. 2 (2025) In Memoriam: Lucio Russo (1944–2025)

Noctua Vol. 12, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Phronesis Vol. 70, No. 4 (2025)

Revue de métaphysique et de morale Vol. 125, No. 3 (2025) Philosophies d'Islam

Enchoria Vol. 38 (2024)

Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol. 84, No. 2 (2025) NB Noga Ayali-Darshan & Guy Darshan "Philo of Byblos’ Version of the Storm God’s Combat Against the Sea"

Iran and the Caucasus Vol. 29, No. 3 (2025)

Zeitschrift des Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft Vol. 175, No. 2 (2025)

The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 87, No. 3 (2025)

Estudios Bíblicos Vol. 83 No. 1 (2025)

Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 144, No. 2 (2025)

Journal of Early Christian Studies Vol. 33, No. 3 (2025)

Scrinium Vol. 21, No. 1 (2025)

Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum = Journal of Ancient Christianity Vol. 29, No. 2 (2025) NB Philip Abbott "Justin the Seer: Viewing Christian Truth in the Second Century"

Speculum Vol. 100, No. 4 (2025) NB Teddy Fassberg "Greco-Arabic Belles Lettres: Reinterpreting the Baghdad Translation Movement"

Mélanges de l’École française de Rome - Moyen Âge Vol. 137, No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

Antiquity Vol. 99, No. 107 (2025) NB Duncan Sayer, et al. "West African ancestry in seventh-century England: two individuals from Kent and Dorset"

Oxford Journal of Archaeology Vol. 44, No. 4 (2025) NB Patrick Sims-Williams "'Celtic Britain' in Pre-Roman Archaeology, Reconsidered"

Workshops, Lectures, and Exhibitions

Next Friday's (October 17th 12:00pm EDT) Schoenberg Institute for Manuscripts Studies (SIMS) Online Lecture features medievalist and book historian J. D. Sargan on Trans Studies as Book Historical Method. His book on the topic, Trans Histories of the Medieval Book: An Experiment in Bibliography, is due to be published at the end of the month by ARC Humanities Press and will be available open access. Also from SIMS, Lisa Fagin Davis's plenary lecture, "Manuscripts on the Move: Exploring the Digital Ecosystem of Manuscript Studies" from last year's 17th Annual Schoenberg Symposium on Manuscript Studies in the Digital Age is now on Youtube.

The California Classical Association focuses on "the origin, the significance, and the reception of Roman, Greek, and related Ancient Mediterranean civilizations." And their Fall 2025 conference, on "Connectivities and Collectivities in Ancient Eurasia," is on October 18, 2025, 9:30 am-1:00 pm. It will be virtually broadcast, so join a great keynote lineup and listen in!