Pasts Imperfect (1.8.26)

This week, we are back from holiday break with a deep dive into the ethics, big business, and myth-peddling of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in higher education. Then, bees in ancient jawbones within the Dominican Republic, Roman camels in Basel, protecting buildings from earthquakes during the Tang and Song Dynasties, a new open access book on Roman temple robberies, a bevy of new podcasts focused on the premodern world, a review of the Met's new exhibition on Divine Egypt, an epic list of new ancient world journals, and much more.

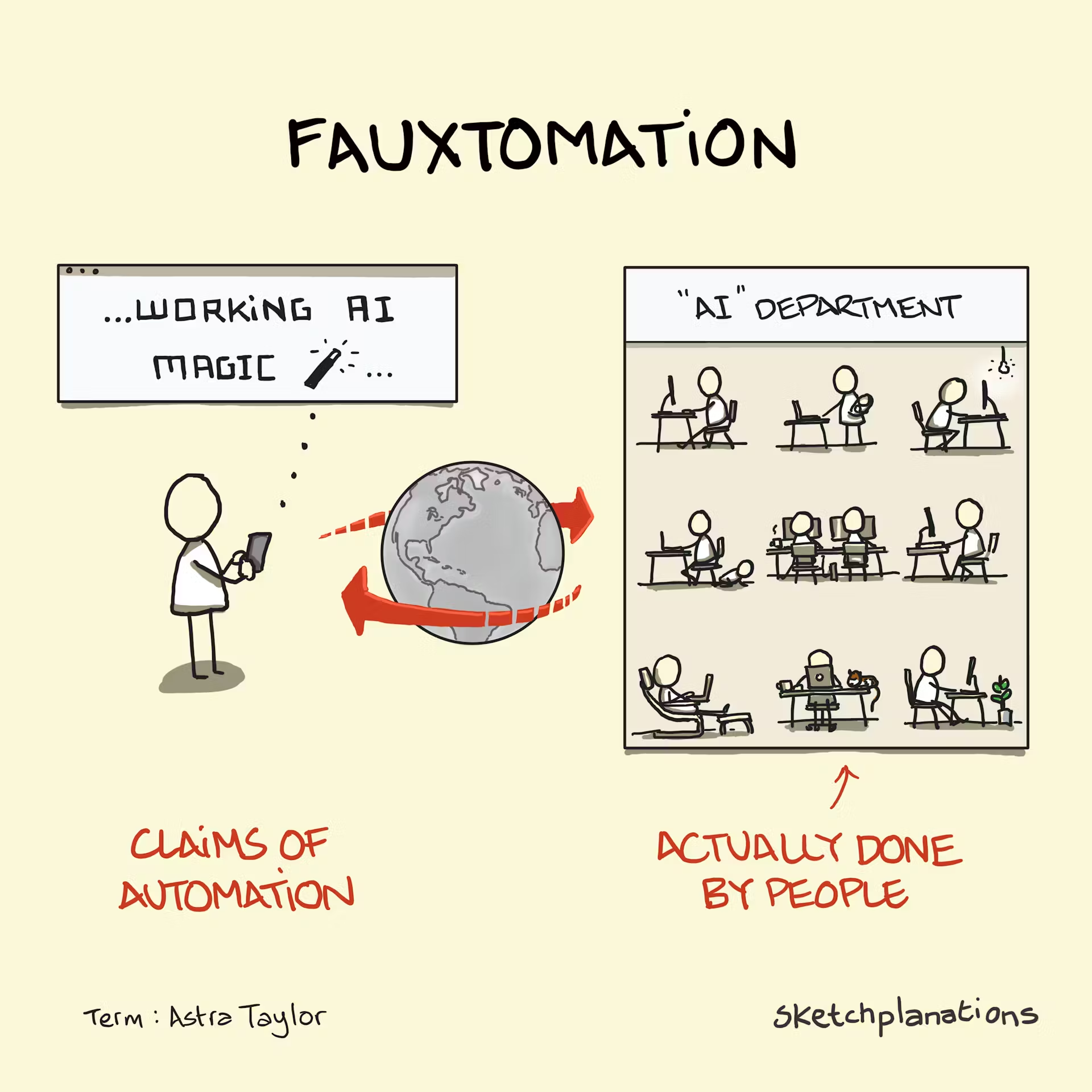

The AI Industry’s Myth of Inevitability: Automating and devaluing literacy in Higher Education

Shortly after the 2024 presidential election, I found myself trying to explain what goes on in the first-year literature seminar I have taught for more than a decade. I detailed how we teach students to really read, to understand texts, and to articulate and interrogate their own and their classmates’ responses to language and ideas. My interlocutor, a fellow academic who had been appointed as a kind of AI czar to their university, was on the lookout for ways to “use AI” in classes like this one. But they had something of an epiphany. “Wow,” they said. “This is hard! You have to think about what each word actually means!”

Attention to text and its meaning are now on the chopping block in American higher education, as universities and colleges rush to endorse commercial software products advertised as able to read, think, and write for you. As programs are closed and austerity reigns, schools are spending money they often claim not to have to help AI companies shore up the balance sheets of an astonishingly money-losing business and then trumpet the institutional endorsements of their largely unproven claims about text generation software. This is what two scholars have called “a case of mutual but unequal reputation laundering.”

Where does that leave scholars of the ancient world? We can choose not to use these tools, but the way our institutions will go right on signing contracts would seem to only validate Big Tech’s claims of our own irrelevance. In the familiar cant of Silicon Valley confidence men, we hear that “AI” is without historical precedent, that “squishy” scholars of humanistic inquiry have little to offer any real conversation about this world-changing technology. But it is precisely historical analogy that can help us understand the real nature and motives of this push.

The “AI” sector’s unabashed push to deskill humans of their literate capacities aims to rewrite the cultural values of our society. The reclassification of certain kinds of labor as unskilled rather than skilled, non-professional as opposed to professional—and thus less worthy of not only compensation but also dignity and rights—is a project of producing new kinds of ontological difference within our society and present it as inevitable.

Producing ontological difference is not a novel technique of control. Thousands of years ago, it was a hallmark of Roman slaving culture, where it was the activities and faculties that most revealed the lack of any natural or “real” difference between enslavers and enslaved that were the sites of some of the most intense efforts to produce and insist on such distinctions. And literate labor was one such site.

Sometime around the end of the third century BCE or the beginning of the second, Roman aristocrats became interested, not only in consuming literature but in owning and producing it themselves. Consequently they began training and educating enslaved people to facilitate that work. A highly developed and widespread culture of enslaved literate labor arose to help Roman elites live (and fashion themselves) as intellectuals; by the final decades BCE, an author like Vergil (d. 19BCE) would have been assisted by a capable staff of enslaved stenographers, research assistants, and readers. Roman intellectuals had become dependent on skilled enslaved assistants who were, in some cases, more knowledgeable or adept than their enslavers.

To manage aristocratic dependence on literary workers, Rome’s enslaving literati policed the difference between what they did as masters and what their enslaved assistants did. Secretaries and stenographers were described as “hands,” as extensions of their enslavers who merely carried out their will. Verbal composition was imagined as something that happened in the privacy of the enslaver’s mind, with its dictation or transcription merely incidental. The philosopher Seneca mocked a wealthy ignoramus who thought he knew the things that his enslaved workers memorized for him; yet in the same passage, Seneca observes that, aside from moral philosophy, “other kinds of intellectual work may be delegated.”

Second century CE essayist Aulus Gellius relates an anecdote in which the philosopher Plutarch orders the beating of an enslaved member of his household who dares to suppose, just because he has overheard books being written and read, that he understands their philosophical content. In other words, capital-R Reading is something masters do, regardless of whether slaves happen to overhear it. Setting these conceptual boundaries reinforced the claims to exclusive cultural capital of Rome’s 1.5%.

The artificiality of these imposed conceptual distinctions is a clue to their purpose. Perhaps discourse and policy that assert loudly the low value of certain kinds of literate capacity may be indicating, by their vociferousness, those capacities that are (and are recognized by those in power to be) of the highest potential value. Roman enslavers insisted enslaved people could not be Authors and Readers in part because of the obvious fact that they were. In the modern economy, basic literacy and the modes of critical thought and expression that draw on it are potent as human faculties that have thus far defied automation. Literate thought and its cultivation confer power, both in political and labor contexts, and the “AI” bubble, with its empty promises of making those capacities obsolete, offers our own ruling classes a chance to permanently discipline and relegate this last unconquered frontier — creative and knowledge work.

Institutional collusion in this project does not solve any existing problem in education, but it does address ruling class anxiety about universities and colleges as places that furnish training in critique and are amenable to dissent. I’m sure my campus is not the only one where suppression of protest against Israel’s ethnic cleansing of Gaza and accelerating institutional AI adoption have come not just in tandem but often at the urging of the same voices. It is the disciplining of intellectual labor, and the permanent relegating of both instructors and faculty, that unites these two drives.

By a similar token, to assert that Large Language Models (LLMs) and their ilk are worth a lot while the humans and human capacities they ingest and mimic are worth next to nothing is not the paradox it seems to be, so long as we understand both claim to share a fundamental premise that anything is preferable to an empowered human workforce. Although the Roman project of redefining the contributions of enslaved literate workers took shape over centuries, the example can help to illuminate the rhetoric of the modern AI marketing project deployed hurriedly over the last few years.

Reflecting on higher ed administrators’ rush to buy into AI, there is perhaps not much mystery behind “austerity”-afflicted universities shoveling money into the AI pit. If we suppose that the idea of cheaper and less empowered labor is as appealing to universities’ administrations and governing boards as it is to for-profit corporations and investors, we see the shift towards the neoliberal “university as business” model at work. But my larger point here is the potential of understanding what is at work around our institutions with reference to our own areas of expertise.

The academy faces, from the “AI” industry, a double assault that seeks to reclassify literate thought as worthless, and to designate as illegitimate any critique or skepticism of that project from humanistic disciplines. Underwriting both moves is often the claim that the times and the technology are unprecedented. But the reclassification, maintenance, and surveillance of intellectual jurisdictions are in fact painfully precedented.

Those rushing to make “AI” a fait accompli hope to redefine human capacities, and extract economic and cultural capital from educational institutions, before the real value proposition and costs of their products become apparent. We should insist not only on our right as faculty to challenge and critique our institutions’ collusion with the companies that threaten our work and our students’ ability to realize their own intellectual potential, but also defend the authority of our own areas of expertise in illuminating this moment.

“When people try to tell you that the future is already settled, it is because it is deeply unsettled,” argues sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom. The intensity of Big Tech’s insistence on the inevitability and superiority of LLM technology, in the academy or anywhere else, indicates not the truth of their claim, but their eagerness for it to be accepted as true without debate or critique. Now is not the moment to acquiesce, but to interrogate and to resist.

Developing AI Literacies through Critical Humanities Teaching

by Christine L. Johnston and Leigh Anne Lieberman

Rapidly evolving digital landscapes and emergent technologies, particularly the growth of generative AI, are creating profound impacts on ancient history research and teaching. Although new technologies offer expanding opportunities for scholarly connection, data analysis and sharing, and multimedia creation, they have also led to concerns over student learning. AI technologies have already made their way into ancient Mediterranean studies classrooms, from tools like Google Translate and audio transcription services to generative AI applications used in fields like primary text translation and linguistic tagging. Furthermore, the recent push for AI adoption within education—and subsequent backlash—highlights the importance of developing critical digital and AI literacies to help students understand the political, social, environmental, and heritage impacts of AI technologies and economies on the study of the past and the world today (the Amherst library has a helpful AI resource guide).

Data and digital literacy training allows us to address many important intersections between AI technologies and the related subfields involved in the study of the past. Historical and anthropological methods, from material and linguistic taxonomies to outdated fields like craniometry and affect recognition, have impacted the structuring of machine learning and computer vision systems, embedding harmful biases into automated algorithmic systems (Johnston 2025). These systems, which are increasingly proving to be “neither artificial nor intelligent” (Crawford, Atlas of AI, p. 8), replicate and amplify the human choices and biases encoded within them.

The racial, social, and economic impacts of automated decision making—what critical information studies scholar Safiya U. Noble has termed “technological redlining” (Algorithms of Oppression, p. 1)—have been documented in all spheres of society, including social programs like housing, child protective services, and healthcare (Eubanks, Automating Inequality), financial lending and employment (Crawford, Atlas of AI), surveillance, policing, and sentencing (O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction), and border and immigration control. The extractive and colonial logics of AI technologies and economies, including data theft, labor exploitation, and environmental depredation (Sadowski, The Mechanic and the Luddite), have led many to view the growth of AI industries as a new form of imperialism (Hao, Empire of AI; Adams, The New Empire of AI).

Integrating data and digital literacy training into our teaching can enhance student learning around the foundational knowledge of the field while preparing learners to evaluate shifting global technologies and economies from critical humanities perspectives. A recent survey of ancient Mediterranean studies faculty showed that there is keen interest in incorporating digital media and tools into our work, however challenges remain around finding accessible and affordable resources and keeping ahead of digital obsolescence (Johnston and Gardner 2024).

To address this growing need, we (Christine Johnston and Leigh Anne Lieberman) will be leading Teaching Ancient in a Digital Age, a virtual and in-person institute running from May through October 2026 (applications accepted through March 6, 2026). This NEH-funded Institute offers ancient Mediterranean studies faculty and advanced graduate students the training needed to facilitate data and digital literacy teaching within our interdisciplinary fields. The institute will also support the development of multidisciplinary open access teaching resources and lesson plans. For more information, please don’t hesitate to contact Christine or Leigh directly.

Public Humanities and a Global Antiquity

Ah, our global antiquity enthusiasts, how we've missed you.

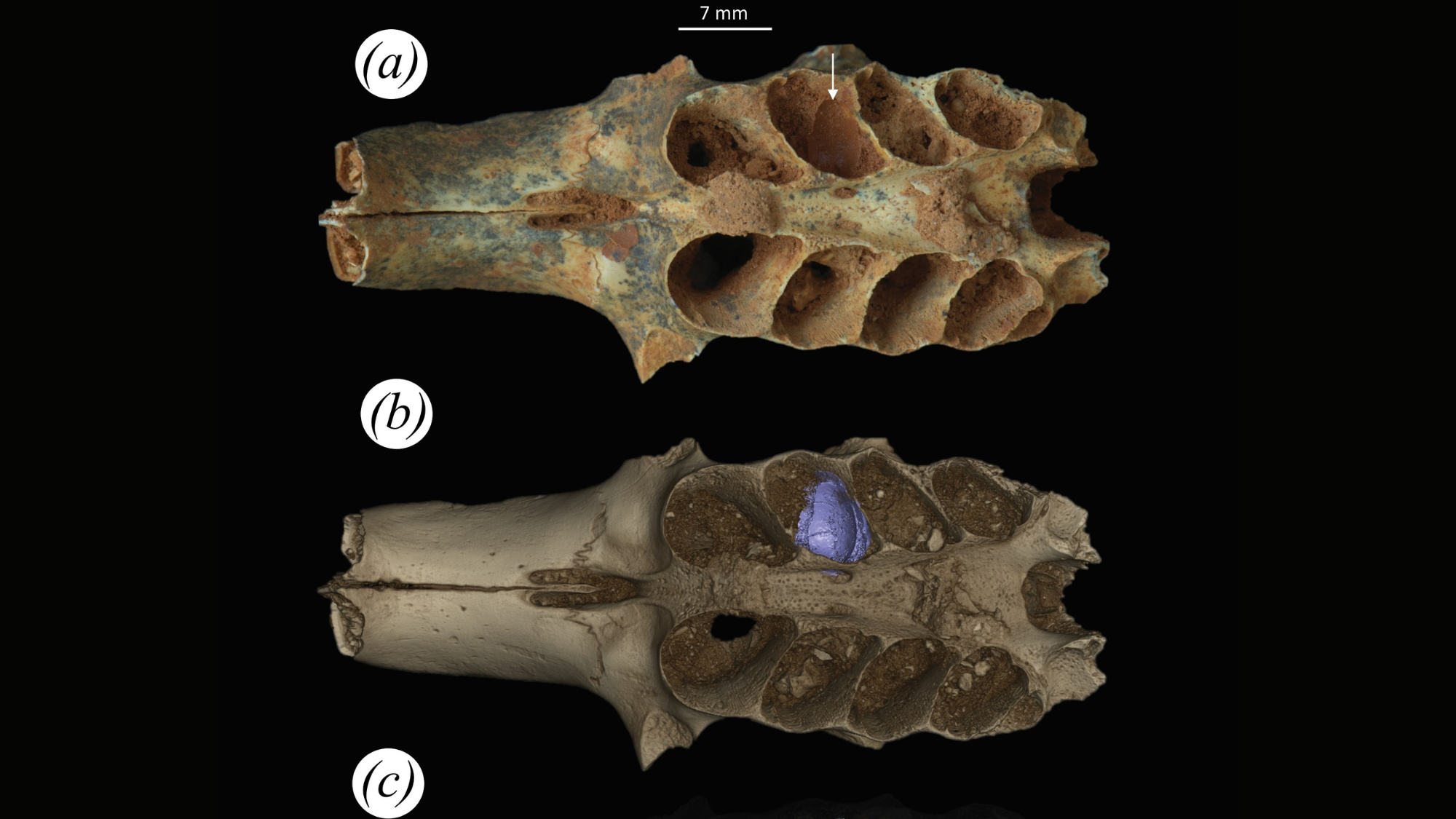

We're diving right back into our news roundup with ... bees in bones. Researchers at the Field Museum in Chicago, IL have discovered burrows of bees in mammal jawbones, hidden away in a cave in the Dominican Republic. The enterprising insects made themselves a "thermos"-like house inside the bones of ancient rodents and sloths, guaranteeing them an extra layer of protection beyond the cells that they built. And in other cool bone news, archaeologists in Switzerland have found late antique camel bones that reveal the Roman use of hybrid camels within what is modern day Basel.

Turns out people have been thinking about earthquake-proofing buildings for a long time. Researchers have found that, during the Tang and Song Dynasties, builders developed increasingly seismic-resistant wooden structures that dissipated energy.

Family drama over the holidays not enough for you? Greta Rainbow at Hyperallergic delivers a review of the Met's special exhibition, Divine Egypt. With over 200 works spanning three millennia, it's worth seeing while it's still up (until January 19).

When I'm free-associating about the Eastern Mediterranean (this happens more than you might think), you can bet that Turkish coffee comes up every other thought. And now, I have another drink to dominate my psyche: menengiç kahvesi, a wild pistachio bevvy which is caffeine-free, nutty, and holistically healthy! Passed down through generations of female healers, menengiç has officially been granted cultural status by the EU for its representation of the southeastern Turkish city of Gaziantep.

Roman literary scholar Isabel K. Köster has a new book out open access with the University of Michigan Press, Stealing from the Gods: Temple Robbery in the Roman Imagination.

Stealing from the Gods investigates how authors writing between the first century BCE and second century CE addressed the issue of temple robbery or sacrilegium. As a self-proclaimed empire of pious people, the Romans viewed temple robbery as deeply un-Roman and among the worst of offenses.

You can download and read it here. Also take a look at her comparison between temple robberies and the Louvre heist at the Michigan Press blog.

The centennial issue of Speculum, the journal of the Medieval Academy of America, offers sixty Speculations on the future of medieval studies. The editors joined the hosts of The Multicultural Middle Ages Podcast to speculate further on the past and future of the field. And over at the Ancient Office Hours podcast, Lexie Henning speaks to Eduardo García-Molina about "his journey from being inspired by the video game 'Rome Total War' to specializing in the Seleucid Empire in his academic career" and much more. And at the New Books in Medieval History pod, Andrea Maraschi and Francesca Tasca explore Food, Heresies, and Magical Boundaries in the Middle Ages (Amsterdam UP, 2024).

New Ancient World Journals by @yaleclassicslib.bsky.social

Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Vol. 65, No. 2 (2025)

AION (filol.) Vols, 46, No. 1-2 (2024)

American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 130, No. 1 (2026) NB Emlyn Dodd "The Archaeology of Olive Oil Production in Roman and Pre-Roman Italy"

Anabasis. Studia Classica et Orientalia Vols. 14-15 (2023-2024) #openaccess

Annali online Unife. Sezione di Storia e Scienze dell'Antichità Vol. 4 (2025) #openaccess

Anzeiger für die Altertumswissenschaft Vol. 78, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Archaeological Reports Vol. 71 (2025) NB Alex R. Knodell "Survey and landscape archaeology in Greece in the twenty-first century"

Aristonothos Vol. 21 (2025) #openaccess

ARYS Vol. 23 (2025) #openaccess Movilidad religiosa en el Mundo Antiguo: John North (1938-2025) & Henk S. Versnel (1936-2025). In memoriam

Boletim de Estudos Clássicos No. 70 (2025) #openaccess

Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz N.S. No. 1 (2025) #openaccess

CALÍOPE - Presença Clássica No. 49 (2025) #openaccess

Classica Boliviana Vol. 14 (2025) #openaccess

Classical Journal Vol. 121, No. 2 (2025-2026)

Cuadernos de Filología Clásica. Estudios Latinos Vol. 45 (2025) #openaccess

Dictynna Vol. 22 (2025) #openaccess

Dionysus ex machina Vol. 19 (2025) #openaccess

Gerión Vol. 43 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess El tratado del río Iber 2250 años después. Diplomacia e imperialismo en el Mediterráneo occidental antigu

Hesperia Vol. 94, No. 4 (2025)

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 12, No. 3 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies Vol. 13, No. 4 (2025)

The Journal of Hellenic Studies Vol. 145 (2025)

Mnemosyne Vol. 78, No. 7 (2025)

New England Classical Journal Vol. 52, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Papers of the British School at Rome Vol. 93 (2025) NB Ronald T. Ridley, "The Great Livy Delusion, 1924"

Ploutarchos Vol. 22 (2025)

Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica Vol. 31, No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Studia graeco-arabica Vol. 15 (2025) #openaccess

Studies in Ancient Art and Civilisation Vol. 29 (2025) #openaccess

Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal Vol. 8 (2025) #openaccess

The Ukrainian Numismatic Annual Vol. 9 (2025) #openaccess

Aristotelica No. 7 (2025) No. 8 (2025) #openaccess

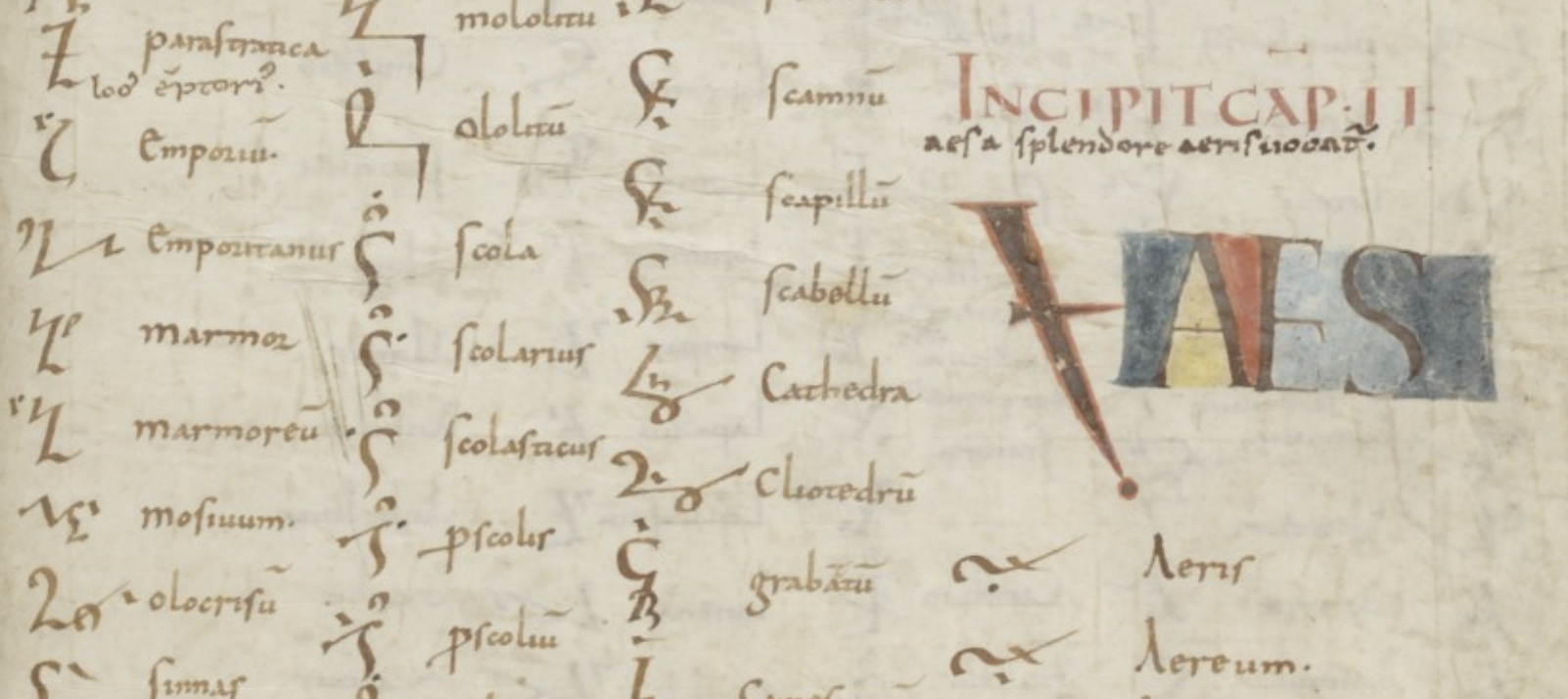

Early Science and Medicine Vol. 30, No. 6 (2025) NB : Claire Burridge. et al. "Early Medieval Medicine: How a New Corpus of Manuscripts Is Transforming the Field"

History and Theory Vol. 64, No. 4 (2025) Philology Now

Journal of World Philosophies Vol. 10 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess NB Ana Laura Funes Maderey, et al. "Diversifying Indic Philosophical Thinking"

Peitho Vol. 16 (2025) #openaccess NB Masaki Nagao, "The Pain of Philosophy: A Cynic Objection to Plato"

Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy Vol. 40 (2025)

Revue de philosophie ancienne Vol. 43, No. 1 (2025)

Aegyptiaca Vol. 9 (2025) #openaccess NB Gabrielle Charrak "Hegel and Champollion: Understanding Egyptian Art through Aesthetics in the Early 19th Century"

Astarté Vol. 8 (2025) #openaccess Usos políticos y memoria de la Antigüedad en los discursos y las narrativas contemporánea

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Vol. 111, Nos. 1-2 (2025)

Journal of Egyptian History Vol. 18, Nos. 1-2 (2025) NB M. Victoria Almansa-Villatoro "The Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period Royal Decrees Revisited: Evidence of Historical and Sociopolitical Change"

Interdisciplinary Egyptology Vol. 2 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess Egyptology in Dialogue: Historical bodies in relations, comparisons, and negotiations

ISIMU Vol. 27 (2024) #openaccess Vida, exploración y comercio más allá del Mar Inferior y el Mar Superior

Libyan Studies Vol. 56 (2025)

Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 88, No. 4 (2025)

Revista del Instituto de Historia Antigua Oriental Vol. 26 (2025)

Journal for the Study of the New Testament Vol. 48, No. 2 (2025) The Future of Revelation and Gender Studies

Journal of Early Christian Studies Vol. 33, No. 4 (2025)

Neotestamentica Vol.59, No. 3 (2025) Early Christian Studies

Patristica et Mediævalia Número especial - 50 aniversario Vol. 46 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Vulgata in Dialogue Vol. 9 #openaccess

Byzantion Nea Hellás Vol. 44 (2025) #openaccess

Das Mittelalter Vol. 30 No. 2 (2025) Sexualitäten im Mittelalter

The Medieval Globe Vol. 11, Nos. 1-2 (2025) Shaping the Nation in Medieval Europe

Médiévales Vol. 89, No. 2 (2025) Routes d'Orient et d'Occident

Scripta Mediaevalia Vol. 18 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Speculum Vol. 101, No. 1 (2026) Speculations: The Centennial Issue

Studia Celtica Fennica Vol. 21 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess Gender and Theory in Medieval Celtic Literature

Traditio Vol. 80 (2025)

Bulletin of the John Rylands Library Vol. 101 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

The Vatican Library Review Vol. 4, No. 2 (2025)

Cuadernos de Prehistoria y Arqueología de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Vol. 51 No. 2 (2025) #openaccess

Journal of African Archaeology Vol. 23, No. 2 (2025

Oxford Journal of Archaeology Vol. 45, No. 1 (2025)

PhDAI. Reports of the Young Research Network Vol. 4 (2025) #openaccess

Exhibitions, Lectures, and Workshops

The Centre for the Study of Medicine and the Body in the Renaissance (CSMBR) in Pisa is putting on an exciting series of online lectures in the coming month. On January 13th, at 5pm CET=11am EST Monica Green will survey "The Transformation of Infectious Disease Histories: Three Decades of Paleogenetics and Historians’ Response," while on the January 28th, also at 5pm CT= 11am EST, Brooke Holmes will discuss "The Tissue of the World: The Ancient History of Sympathy."

On Wednesday, January 14th at 4:15 pm CET=10:15 am EST, the latest installment of the online lecture series "Digital Coptic Studies" features So Miyagawa, presenting:" THOTH.AI: a Large Language Model for Ancient Egyptian and Coptic." The series commemorates ten years of work on the Digital Edition of the Coptic Old Testament.

The Institute for Classical Studies on January 21st at 3 pm GMT = 10am EST will host an online workshop on "Publishing your research in Classics and Archaeology journals." The editors of Journal of Roman Studies, Classical Philology, Annual of the British School at Athens and Polis will demystify the publishing process.